Field Report: Manitowish Waters Labor Day weekend rice camp

Field Report: Manitowish Waters Labor Day weekend rice camp

Every fall for hundreds of years, families and tribes have gathered for wild rice season on the lakes and streams of what is now known as northern Wisconsin. For the Anishinaabe—including Ojibwe and other related tribes—this annual gathering remains a vital cultural and social tradition, encompassing far more than food gathering.

Manoomin is not simply a “food that grows on water.” At the heart of tribal beliefs, it is recognized as a Sacred Living Being—and, unfortunately, it is very much under threat.

This year, following in the rice camp tradition, GLIFWC and UW–Trout Lake Station hosted an intergenerational, intertribal Manoomin/Manōmaeh (“Wild Rice”) Camp over Labor Day weekend at the North Lakeland Discovery Center in Manitowish Waters. Esiban Parent (GLIFWC), Sagen Quale (UW graduate student), and Dr. Gretchen Gerrish (UW–Trout Lake Station) did an outstanding job organizing the event.

Rice camp is a deeply hands-on experience—a time when wisdom and knowledge about harvesting, processing, and cooking wild rice are passed down each fall. Because Manoomin is regarded as a Sacred Being, the camp also includes ceremony and other cultural practices that can only be learned firsthand or by invitation.

There are no spectators at rice camp—your moments are spent either learning, teaching, or building the tools essential for traditional wild rice gathering (or “ricing”). All the while, participants are storing and sharing knowledge that keeps this living tradition thriving.

The basic process of preparing wild rice begins with the harvest. Gathering wild rice is done from a canoe using a push pole, a pair of rice knockers, and two people working together. After harvesting, the rice is spread out in the sun to dry, giving rice worms and spiders a chance to leave before processing begins.

The traditional process of preparing wild rice involves three main steps: parching, threshing (also known as “dancing the rice” or “jigging”), and winnowing.

Parching—or roasting—dries the grain to preserve it and makes the hull brittle. Threshing removes the dried husks from the kernels, traditionally done by “dancing” or “jigging” on the rice. Winnowing uses wind to separate the loose, light chaff from the heavier, processed rice grains. At that point, you have ready-to-cook rice. All of these activities took place at this year’s camp, along with workshops where participants hand-crafted their own traditional ricing tools.

“Whether I was carving rice knockers, building push poles, crafting birchbark baskets, enjoying delicious manoomin meals, or paddling through rice beds, my experiences at Rice Camp helped cement my connection to the unique and valuable waters we have right here in Wisconsin, and strengthened my resolve to continue to protect them.” – Evan Arnold, River Alliance Development Director

Saying rice camp is the heart and soul of Manoomin is a bit simplistic, but it is certainly appropriate. For anybody wanting a deeper connection to our world, or seeking new ways to grow your stewardship, a single weekend at rice camp can easily unlock a lifetime pursuit and passion.

Please consider attending a rice camp next year, whether this camp in 2026 or another rice camp in the upper Midwest in September and October. Learn how to become a Manoomin Steward volunteer with River Alliance of Wisconsin and subscribe to our ManoomiNews newsletter today to get future stories like this one and more delivered to your inbox.

This message is made possible by generous donors who believe people have the power to protect and restore water. Subscribe to our Word on the Stream email newsletter to receive stories, action alerts and event invitations in your inbox. Take a deeper dive into the topic of manoomin by subscribing to our ManoomiNews newsletter. Support our work with your contribution today.

The post Field Report: Manitowish Waters Labor Day weekend rice camp appeared first on River Alliance of WI.

Blog - River Alliance of WI

https://wisconsinrivers.org/2025-intertribal-rice-camp-report/

I’m in a new role as “She Who Takes Care of the Wild Rice,” our most precious gift. Peter and Lisa David previously worked with the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission as wildlife and Manoomin biologists and retired about three years ago. GLIFWC reorganized and created two roles: wetland ecologist and my position that integrates traditional knowledge and culture to build relationships with rice chiefs and tribal communities to give a voice to manoomin.

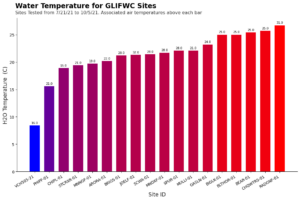

I’m in a new role as “She Who Takes Care of the Wild Rice,” our most precious gift. Peter and Lisa David previously worked with the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission as wildlife and Manoomin biologists and retired about three years ago. GLIFWC reorganized and created two roles: wetland ecologist and my position that integrates traditional knowledge and culture to build relationships with rice chiefs and tribal communities to give a voice to manoomin.  How I see it, manoomin are other beings that experience how the weather can shift in our seasons. It’s happening today. Climate change has extreme water fluctuations, from extreme rain and flooding, to less snowpack and droughts. This impacts rivers and streams, which shifts the channels of water going into rice water bodies. When there is a slower movement of water, we see things like lily pads and other native plants encroaching on rice. Those who work with manoomin recognize its sensitivity. We have estimated that nearly half of the historic range of manoomin has been lost due to habitat loss, decreased water quality and human activity where it had once thrived for thousands of years.

How I see it, manoomin are other beings that experience how the weather can shift in our seasons. It’s happening today. Climate change has extreme water fluctuations, from extreme rain and flooding, to less snowpack and droughts. This impacts rivers and streams, which shifts the channels of water going into rice water bodies. When there is a slower movement of water, we see things like lily pads and other native plants encroaching on rice. Those who work with manoomin recognize its sensitivity. We have estimated that nearly half of the historic range of manoomin has been lost due to habitat loss, decreased water quality and human activity where it had once thrived for thousands of years.  Non-tribal members can play a crucial role in protecting manoomin. They can contribute by learning and respecting our indigenous knowledge, but they have knowledge themselves that they can share. It can be a cultural exchange. They can educate themselves about the cultural significance of manoomin to our communities, especially to Ojibwe people, and learn about the spiritual and ecological importance of this native grain. They can advocate for legal protections and support initiatives like the Rights of Manoomin like Minnesota is doing. They can advocate for legal protections in other parts of the state.

Non-tribal members can play a crucial role in protecting manoomin. They can contribute by learning and respecting our indigenous knowledge, but they have knowledge themselves that they can share. It can be a cultural exchange. They can educate themselves about the cultural significance of manoomin to our communities, especially to Ojibwe people, and learn about the spiritual and ecological importance of this native grain. They can advocate for legal protections and support initiatives like the Rights of Manoomin like Minnesota is doing. They can advocate for legal protections in other parts of the state.