Species Spotlight: Chestnut Lamprey

This month’s species spotlight shines light on a native lamprey species of the Winnebago System: Chestnut Lampreys (Ichthyomyzon castaneus). There are other native species of lamprey in the Winnebago System too. These are the Silver, American Brook, and Northern Brook lampreys. Chestnut and silver lampreys are parasitic as adults, feeding on fish. However, this usually does not kill the fish. Despite the scary looking sucker disks, native lampreys are an important part of the ecosystem.

Chesnut Lamprey (young) Photo Source: Cal Yonce/USFWS

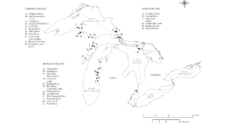

However, there is a non-native lamprey species to be aware of too: the sea lamprey. The sea lamprey is an aquatic invasive species has not invaded the Winnebago System, but is present in the Great Lakes. If the sea lamprey were to invade the Winnebago System, it is likely they would cause major issues for the ecosystem. We must work hard to keep this aquatic invasive species out of the Winnebago System. Though a bit creepy looking, the chestnut lamprey (and Silver, American Brook, and Northern Brook lampreys) are native to this region.

Chestnut lampreys are parasitic as adults but not as larvae. The adult chestnut lamprey attaches to a fish, then scrapes a hole in the body and sucks out blood and tissue fluids for nutrients. After feeding on a fish for several days, the lamprey drops off. Usually, the fish is not killed directly by the attack, but may die due to infections from the wound.

Chestnut lampreys have a skeleton made of cartilage with no true vertebrae. They technically do not have a jaw. This makes lampreys different from eels, which have a bony skeleton and jaws. Lamprey bodies are long and cylindrical. Chestnut lamprey adults range in length from 5-11 inches. The mouth of adult chestnut lampreys is as wide or wider than the head, and contains sharp teeth that each have two points (bicuspid). Along their back, chestnut lampreys have one continuous fin. Adults are usually dark brown, gray, or olive-green on the top, with a lighter coloration of yellow or tan on the stomach. During spawning, they can appear blue-black. Younger lampreys tend to be lighter in color.

The native range of the chestnut lamprey is as far north as the Hudson Bay in Canada and as far South as the Gulf of Mexico. The Mississippi and Missouri River networks help with this large range, as the lampreys move with their host fishes.

Chestnut Lamprey (bottom; native) vs. Sea Lamprey (top; non-native; NOT found in Lake Winnebago)

Photo Source: Bobbie Halchishak/USFWS

Chestnut lampreys spawn in late spring when the water temperature is about 50ۧ°F. Chestnut lampreys stay in the larval phase for 3 – 7 years. Chestnut lamprey larva do not have eyes. When they hatch, chestnut lampreys move downstream and bury themselves at the bottom of the water body they’re living in. For the next few years, they filter feed on tiny algae particles and tiny organisms before beginning to develop their sucking disk. This disk develops teeth which allows for parasitic feeding. Once Chestnut Lampreys are adults, they can suck blood and other nutrients from host fish. Chestnut lampreys can feed on many different fish species including carp, trout, pike, sturgeon, catfish, sunfish, and paddlefish. They live another one to two years as adults, for a total lifespan of about 6 – 9 years.

Chestnut lampreys are primarily nocturnal, meaning they are most active at night. This is often why we don’t see them unless they are attached to fish we catch! During the day, they rest under rocks and along river banks. Adult chestnut lampreys are not known to have predators, but the larval lampreys are preyed upon by burbot and brown trout.

Though we tend to think of parasites as “bad”, they play an important role in the ecosystem including helping to remove weaker fish from the population. The lamprey population may become large when they have plenty of fish to feed on, but then decrease as host populations decrease. This cycle is normal in the ecosystem. Aquatic invasive species like the sea lamprey are a cause for concern because they interfere with normal population dynamics.

Article written by Katie Reed, Winnebago Waterways Coordinator: katherine@fwwa.org

Featured Image Credit: Great Lakes Fisheries Commission

Additional Image Credit 1: Cal Yonce/USFWS

Additional Image Credit 2: Bobbie Halchishak/USFWS

Sources:

Lampreys of the Great Lakes – Great Lakes Fishery Commission

Chestnut Lamprey – Illinois DNR

Ichthyomyzon castaneus – Chestnut lamprey – Animal Diversity Web

Winnebago Waterways is a Fox-Wolf Watershed Alliance recovery initiative. Contact us at wwinfo@fwwa.org

The post Species Spotlight: Chestnut Lamprey appeared first on Fox-Wolf Watershed Alliance.

Fox-Wolf Watershed Alliance

https://fwwa.org/2023/08/25/species-spotlight-chestnut_lamprey/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=species-spotlight-chestnut_lamprey