Stormwater infrastructure tour puts the ‘green’ in Green Bay

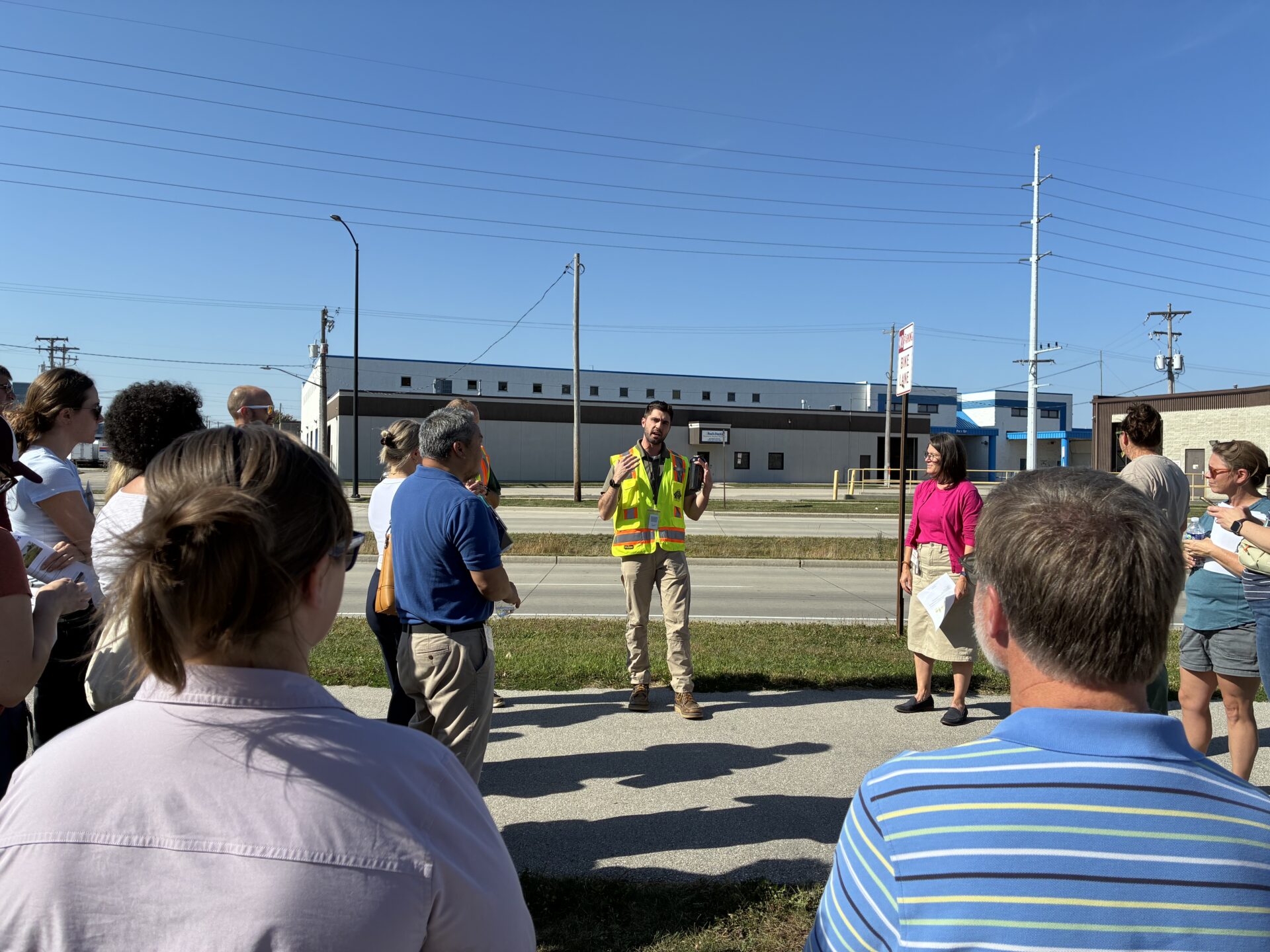

On October 2, a tour group with the East River Collaborative gathered on Webster Avenue in Green Bay, Wisconsin, to learn how the median, bristling with native grasses and late-season blooms, serves as both a sponge and spot of beauty along this busy stretch of road.

“These plant species offer aesthetic value. They also offer pollinator habitat,” explained Adam Meade, a stormwater engineering technician with the city of Green Bay who maintains the median. “And the real key thing is that they treat stormwater.”

The shallow, vegetated depressions, known as bioswales, were one stop on the East River Collaborative’s tour of green stormwater infrastructure projects across the city. The event brought together local municipalities and environmental organizations to learn about natural ways to slow, absorb, and treat runoff. For Wisconsin Sea Grant’s Julia Noordyk, who helped organize the tour, it was a showcase of possibilities.

“We wanted to give people the opportunity to see green stormwater infrastructure in person and ask questions about the design, costs, and lessons learned,” she said. “These projects are possible, and they can take many forms.”

Adam Meade explains the Webster Avenue bioswales, which are located in the median of the road behind him. Photo: Wisconsin Sea Grant

Unlike traditional infrastructure, which relies on impermeable surfaces like pipes, gutters, and ditches to transport stormwater away from other impermeable surfaces like roads and parking lots, green stormwater infrastructure mimics the way water moves in nature and encourages it to soak into the ground where it falls. That absorption is a good thing. It means fewer contaminants running into waterways and — key to the East River Collaborative’s mission — less flooding.

The collaborative formed in response to historic flooding of the East River in March 2019, which impacted both Green Bay and neighboring communities. Since then, the group has brought together municipal, state, federal, nonprofit, and university partners to build resilience to floods across the East River Watershed. Much of their work revolves around education so partners feel empowered to make choices that make sense for their communities.

“We really want to use this platform to share knowledge and expertise and funding sources with each other,” said Kari Hagenow, a coastal resilience specialist with The Nature Conservancy who helped plan the tour. “So, building the capacity of our partners — that’s what the focus is today.”

The field tour stopped at four locations across Green Bay — the NEW Water campus, Webster Avenue, Eliza Street, and Danz Park — and showcased three different types of green stormwater infrastructure.

Bioswales

A car drives past the bioswales. Photo: Wisconsin Sea Grant

Built in 2019 as part of a multimillion dollar road reconstruction project, the seven bioswales stretch nearly a mile along Webster Avenue. Curb cuts allow runoff from the road to flow into the shallow depressions, where native plants soak up water and filter contaminants that would have otherwise run directly into storm sewers. The bioswales relieve pressure on the stormwater system and offer natural beauty along one of Green Bay’s main thoroughfares.

They do require some maintenance. “[The bioswales] are the low points of the road,” Adam Meade said. “They’re going to collect all the runoff. So, what that means too is all the trash and debris and sand.”

Increased maintenance in spring, however, is offset by lower maintenance needs in summer. Unlike conventional turf grass medians, the bioswales only require occasional mowing along the borders so plants don’t encroach on the road.

Permeable pavement

A section of NEW Water’s parking lot is permeable pavement. Photo: Wisconsin Sea Grant

Pavement that allows water to run through it, rather than over it, was on display at two sites on the tour. NEW Water, the brand of the Green Bay Metropolitan Sewerage District, recently installed 2,200 square feet of permeable pavers in its parking lot. Water flows into spaces between interlocking pavers, where it filters through several layers of gravel before entering the storm sewer.

The Eliza Street pavers, located at the bottom of a hill in a residential neighborhood, are a different brand but function similarly. They can capture over 1,000 inches of rain per hour, storing and cleaning runoff before it enters the Fox River.

Both systems require annual vacuuming to remove debris clogging the spaces between pavers. Winter also presents challenges, as salt and snowplows can damage the pavers, so special care is taken when clearing these areas.

Native plants

The Danz Park prairie plants. Photo credit: Wisconsin Sea Grant

Deep-rooted prairie plants are good at soaking up water — and look good while doing it — which makes them suitable for managing runoff and beautifying spaces. In addition to their permeable pavement project, NEW Water showed off their recently seeded prairie, which replaces 1.2 acres of turf grass. Jeff Smudde, director of environmental programs, explained that the planting is part of an effort to increase water infiltration across their properties, of which 46% is impervious.

“We can demonstrate that not only do we talk a good talk, but we walk the walk as well,” he said.

The aesthetic benefits of native plants were clear at Danz Park, the final stop of the tour. Parks Director Dan Ditscheit explained how the city worked with the Green Bay Conservation Corps to install 9,400 prairie plants around Century Grove, an area of 100 trees that commemorates the department’s 100th anniversary. The plants replaced an area of weed-choked wood chips.

“What’s nice about this scenario is that it doesn’t take a lot of maintenance other than coming in and weeding it every so often,” said Ditscheit. “And it reduces the amount of turf that we have to mow on an annual basis.”

The plants are arranged in artful rings and look more landscaped than a traditional prairie. Maria Otto, conservation corps coordinator, said that was intentional to challenge “the misconceptions of native plants looking weedy or wild.” The plantings have attracted attention from neighbors and wildlife alike.

“We actually have homeowners calling us, like, ‘What plants do you have at that site?’” Otto said. “We have a meadow blazing star here, and on one blazing star, there were 10 monarch butterflies.”

***

The University of Wisconsin Aquatic Sciences Center administers Wisconsin Sea Grant, the Wisconsin Water Resources Institute, and Water@UW. The center supports multidisciplinary research, education, and outreach for the protection and sustainable use of Wisconsin’s water resources. Wisconsin Sea Grant is one of 34 Sea Grant programs supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in coastal and Great Lakes states that encourage the wise stewardship of marine resources through research, education, outreach, and technology transfer.

The post Stormwater infrastructure tour puts the ‘green’ in Green Bay first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/news/stormwater-infrastructure-tour-puts-the-green-in-green-bay/

Explore the intersection of science and writing about the Great Lakes during a science café at 6-9 p.m., Nov. 8, Paradise North Distillery (101 Bay Beach Road, Suite 5) in Green Bay.

Explore the intersection of science and writing about the Great Lakes during a science café at 6-9 p.m., Nov. 8, Paradise North Distillery (101 Bay Beach Road, Suite 5) in Green Bay.

“Sea Grant’s success and impact continues to rely on the power of collaboration,” said Jonathan Pennock, director of the National Sea Grant College Program. “This special issue showcases and celebrates the breadth of Sea Grant’s work.”

“Sea Grant’s success and impact continues to rely on the power of collaboration,” said Jonathan Pennock, director of the National Sea Grant College Program. “This special issue showcases and celebrates the breadth of Sea Grant’s work.”