Marine debris play script available for free

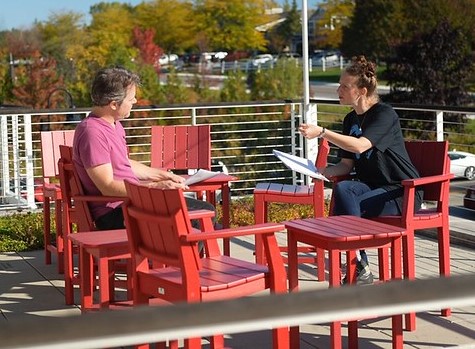

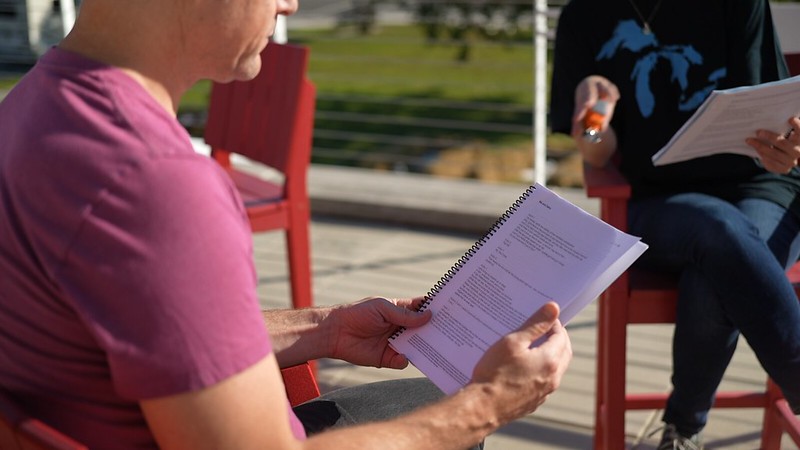

Actors Neil Brookshire and Cassandra Bissell practice their lines for “Me and Debry,” a play about marine debris held at the Door County Public Library in 2022. Image credit: Bonnie Willison, Wisconsin Sea Grant

What is marine debris, what are its impacts and what can we do about it? These are the central messages of a play written on behalf of Wisconsin Sea Grant by David Daniel with American Players Theatre of Wisconsin.

“Me and Debry,” (pronounced “debris”), is a half-hour, whimsical, audience-participation play about litter (marine debris) in the Great Lakes. It had its “world premiere” in Wisconsin’s Door County in October 2022 and was performed three times at the Gilmore Fine Arts School in Racine, Wisconsin, for fifth- and sixth-grade students in May 2023.

The play’s script has been fine-tuned through these performances and is now available for others to use for free, complete with props.

Ginny Carlton, Wisconsin Sea Grant’s education outreach specialist, recently discussed the play and why schools or other educational institutions might be interested in performing it.

Ginny, what is marine debris and what message does the play offer about it?

So, a lot of times people think about gasoline or oil on the water because we often see that on the news. Technically, from NOAA’s perspective (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration), that isn’t marine debris. It’s obviously pollution, but the definition requires marine debris to be a solid. It can be anything from something really small, like a microplastic, to something quite large, like a derelict fishing vessel.

Often, environmental messaging can be sort of depressing and doom and gloom. We wanted to provide students with an uplifting message. One of the lines in the play is, “If it’s to be, it’s up to me.” This particular line is repeated a couple times during the play, so that hopefully, the students come to understand that they can have a positive role in at least considering what to do and making a change that would have a positive impact.

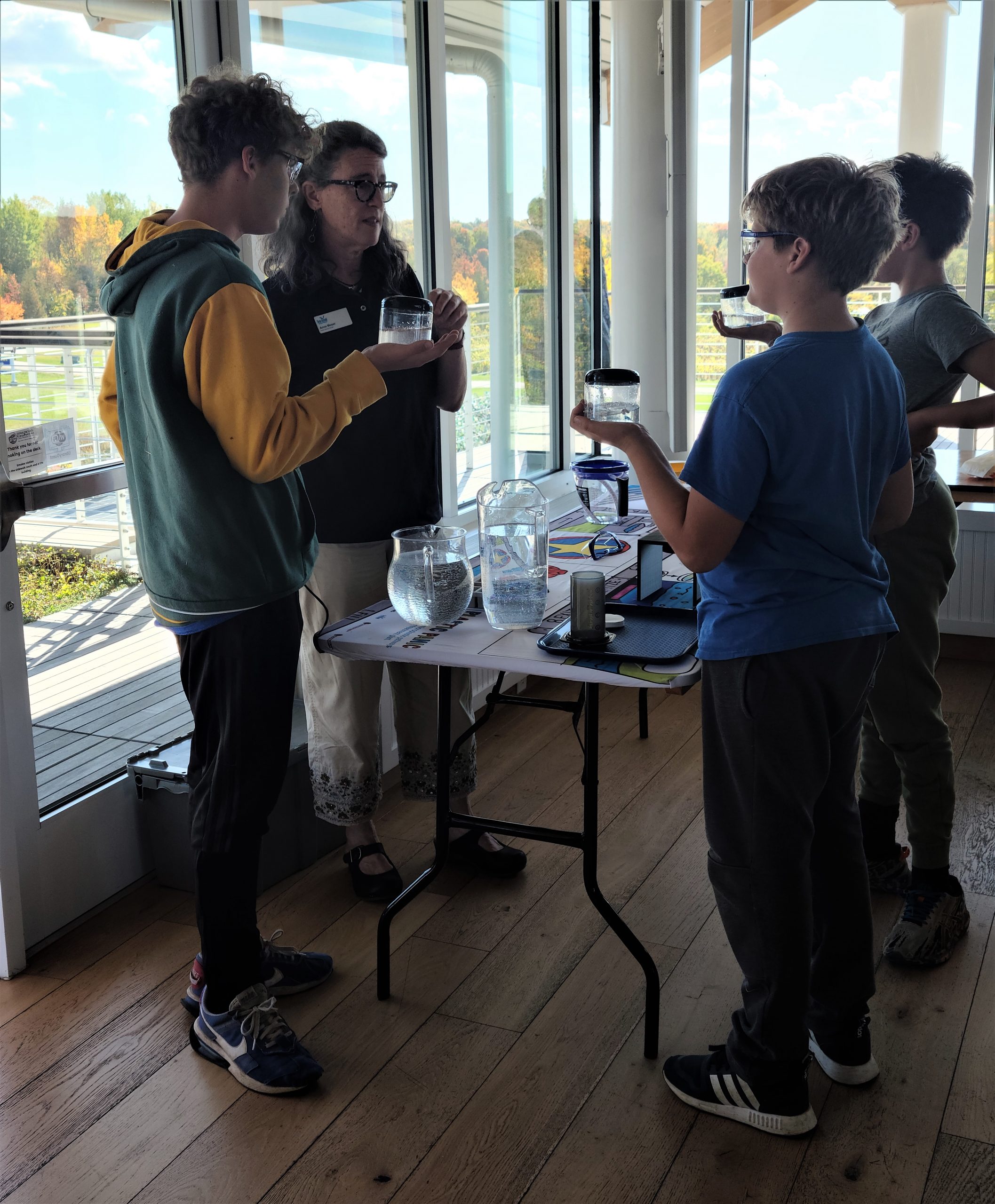

Ginny Carlson (left) instructs Racine elementary students in an environmental stewardship day project at Quarry Lake County Park as part of the marine debris project that the “me and Debry” play came from. Image credit: Bonnie Willison, Wisconsin Sea Grant

What is special about the play compared to other marine debris educational materials?

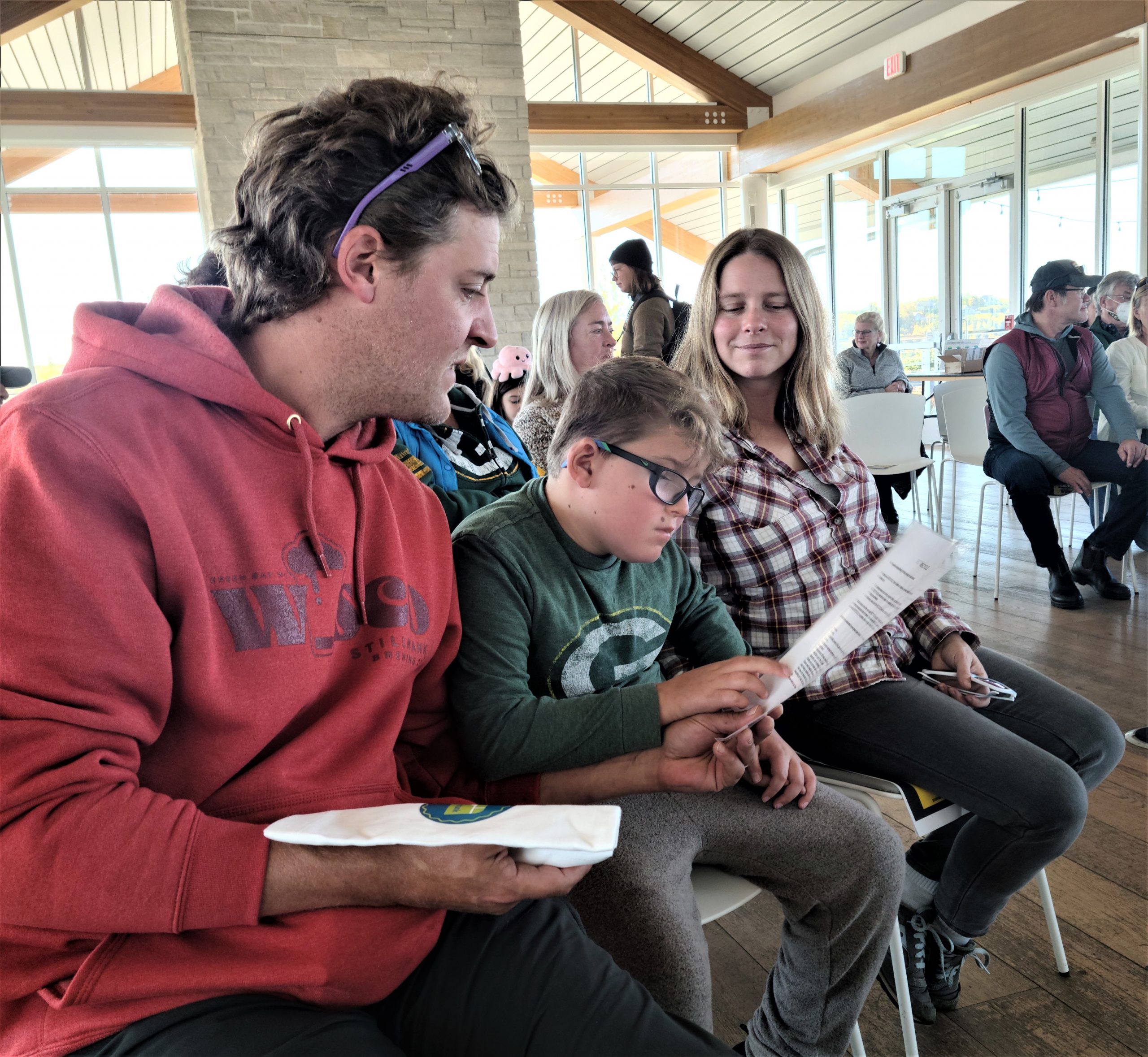

Two reasons: one, it presents the material in a slightly different messaging format. Rather than reading a textbook or watching a video, it has an opportunity for interaction. There’s a lot of audience participation built into the play script. There are four central roles that are performed by members of the audience. One is a crane, another is a kayaker, a fish and a kid. Then beyond those four central roles, there’s also audience participation opportunities when the play starts to talk about what we call the eight R’s. Many teachers and students are already familiar with three of the R’s. Reduce, Reuse, Recycle. The play introduces five others for the students and the educators to think about. (Rethink, Refuse, Repurpose, Refurbish and Repair)

I think another reason is that it has the potential of getting people up moving and actually doing, and inspiring action beyond the actual performance. So, providing an opportunity for the students to consider their own behavior and their own impact on this issue and potentially making some minor adjustments in what they’re doing. Obviously other educational curriculum and formats also attempt to do that, but for some reason, I think just having the audio and visual together and having live interactions with people brings it one step further along than just listening to a teacher talk about it or with a PowerPoint or watching a video, perhaps.

Also, the script design itself is a rhyming format, and that tends to grab people’s attention, and it somehow helps people to remember the content better than just having it in regular prose.

Do actors in the play need to memorize lines?

Even with the actors that were at Door County and in The Gilmore Fine Arts School, we told them that there was no need for them to memorize lines. They could do what they called a reading performance, which means that you can have the script in hand. The desire is to have you pre-read it, so you’re not standing and reading like a storybook-style program, but that you have some familiarity with the script ahead, but have it there to provide a refresher as you move along.

What do students get out of the play in addition to marine debris education?

Students get an opportunity to do some public speaking. I think oftentimes students don’t have the opportunity to publicly speak in front of their peers and or other individuals. So that can be a real confidence-booster to have the opportunity to do that.

They also have an opportunity to consider different worldviews and different perspectives. So, by including the characters of the crane and the fish our intention and hope was that perhaps the students or youth that are watching the performances and interacting with the performances would understand how humans can and do impact other organisms and our responsibility to them — a stewardship message that is part of the play as well.

The “Me and Debry” script is now available to use for free. Image credit: Bonnie Willison, Wisconsin Sea Grant

How do people get the script if they want it?

The easiest way to obtain it is to simply download it from our Wisconsin Sea Grant Education website. We have it available in English, and then the four main character parts for the audience members are in English, Spanish, and Hmong translations as well. The eight R materials for audience participation, they’re available in English, Spanish, and Hmong directly from our website. We also include all that material in a costume kit and an educational kit that you can make a request to have sent to you within Wisconsin. That link is also on the education website. So, you simply make a request for the materials to be interlibrary loaned to you.

The kit has costumes for the two primary actors. Basically, a T-shirt and a pair of oversized sunglasses, so it’s not elaborate costuming. And similarly, it has costumes for the four main characters. And then supporting props for the various eight R topics.

Does it cost anything?

No. Just like our other educational kits at this time, there’s no charge. We will ship it on our cost, and we also pay for the return shipping.

Me and Debry, is part of a two-year project funded by Wisconsin Sea Grant with grants from the National Sea Grant College Program, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Debris Program, U.S. Department of Commerce, and the state of Wisconsin.

The post Marine debris play script available for free first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/news/marine-debris-play-script-available-for-free/

If you’re among the many who are looking for online learning materials for use at home, you might want to check out the Trash Trunk. This new learning kit focuses on trash found in our waterways, otherwise known as marine debris. Its free lessons are applicable for learners at levels kindergarten through adult in both formal and informal educational settings.

If you’re among the many who are looking for online learning materials for use at home, you might want to check out the Trash Trunk. This new learning kit focuses on trash found in our waterways, otherwise known as marine debris. Its free lessons are applicable for learners at levels kindergarten through adult in both formal and informal educational settings.