Door County shipwreck listed on National Register of Historic Places

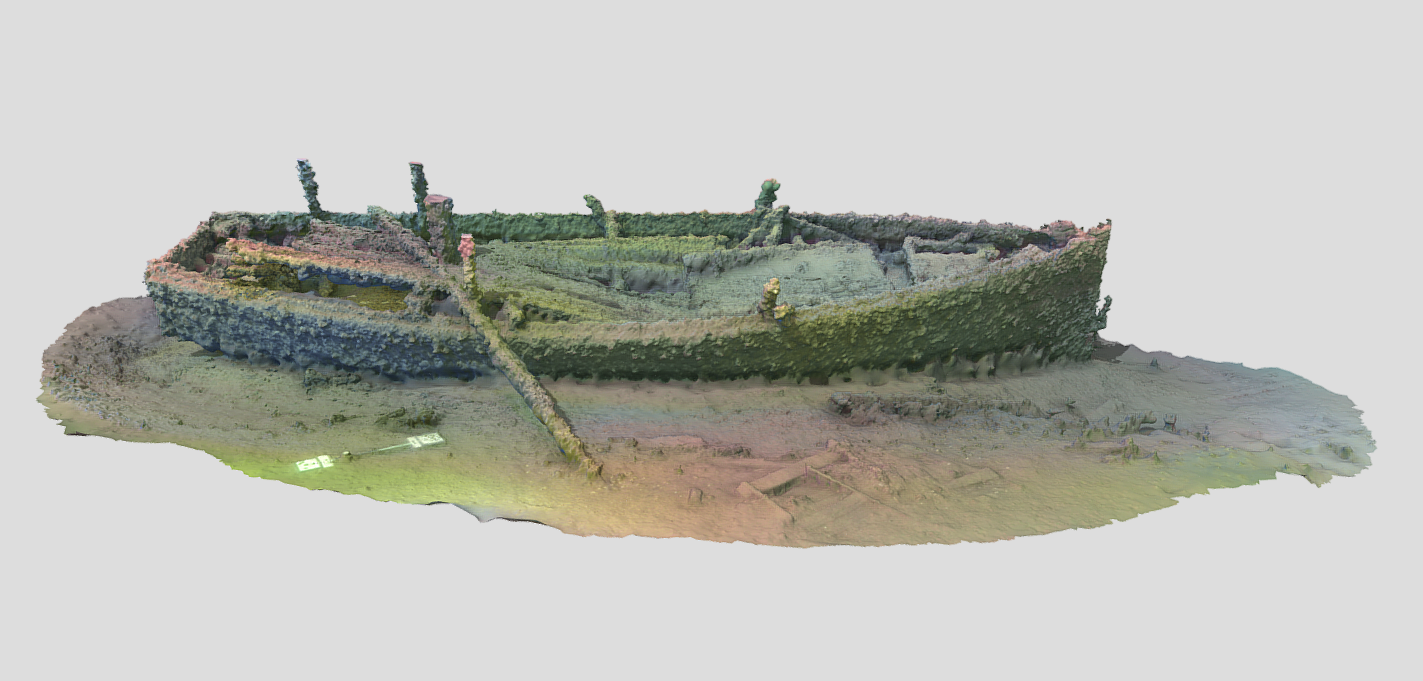

Photogrammetry model of the Little Harbor launch. Image: Zach Whitrock

The Little Harbor launch wasn’t a muscular ship. Measuring nearly 30 feet in length, the boat paled in comparison to the hundred-foot steam-powered vessels ferrying lumber and coal across Lake Michigan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But this little boat, wrecked off the coast of Door County and newly listed on the National Register of Historic Places, can tell us a lot about the history of one of Wisconsin’s favorite vacation spots.

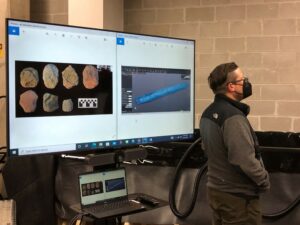

Marine archaeologist Tamara Thomsen led the effort to survey and register the vessel as part of her Sea Grant-funded research on shipwrecks in the bay of Green Bay. Her team was the first to visit and document the launch, which was uncovered during a NOAA coastal survey in 2021.

“Being able to be the first there helps give the full story, or as much of the story, as we can gather from the shipwreck,” Thomsen said. “It’s our first chance to look at it and do the archeological examination before others come and may end up inadvertently damaging the site.”

It’s also the first time this type of story is being told. Not much is written about small, powered watercraft in Great Lakes maritime history.

“We’ve spent a lot of time in this office looking at large commercial vessels – you know, schooners and steamers. They were this major part of the transportation network on the Great Lakes,” said Thomsen. “But we haven’t had the opportunity to study these small, what are called ‘vernacular’ craft.”

Unlike schooners and steamers, launches were everyday boats for everyday people. They were used for pleasure boating and fishing, and they also transported both vacationers and fruit pickers around the oft-visited Door County peninsula.

“Every one of the little resorts along Door County had a launch,” Thomsen said. “When folks would come into Sturgeon Bay, the small resort would go and pick them up with the launch. Cherry pickers were moved around the peninsula by launch. You have to remember that the trains really didn’t get to the northern part of Door County until the 1920s.”

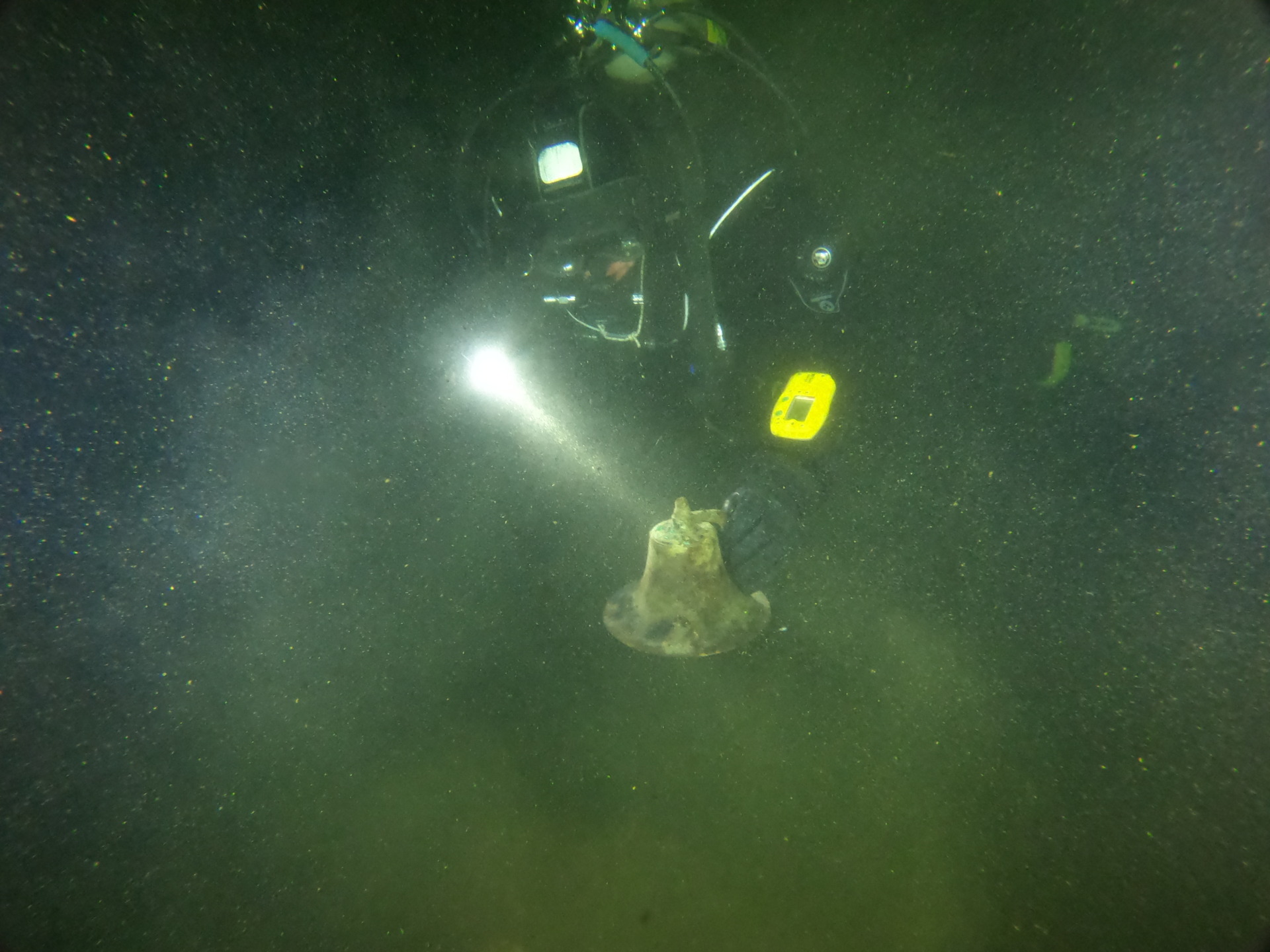

Diver Tim Pranke holds up the bell from the shipwreck of the Little Harbor Launch. Photo: Wisconsin Historical Society

Often these launches were built locally. Tim Pranke, a seasoned diver and engine enthusiast who volunteers on Thomsen’s dives, helped identify the Little Harbor’s gasoline engine as one built by Straubel Machine Company in Green Bay. That’s not a surprise given the vibrant boat-building industry in the state. In the early 1900s, Wisconsin was the third largest manufacturer of non-steam powered launches in the country.

Some things still remain a mystery, though, like the identity of the launch and why it sank. Thomsen and team pored through local papers looking for news of a boat matching the description of the launch, but to no avail. It’s unusual for a place like turn-of-the-century Door County where, Thomsen said, if someone in the boat business so much as “sneezed, it showed up in the newspaper.”

The boat may remain anonymous, but that doesn’t mean it’s unimportant. Big ships can tell us about trade and tycoons, but boats like the Little Harbor launch can tell us about everyday folks — the ones picking cherries or casting a line.

Said Thomsen, “It fills out the story of people’s use of the waterway.”

The post Door County shipwreck listed on National Register of Historic Places first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/news/door-county-shipwreck-listed-on-national-register-of-historic-places/