The Swale Tale

How an unusual Door County landscape is helping researchers learn how Great Lake water levels affect groundwater and forests in coastal areas

Landscapes tell a story. That can be obvious to the casual observer traveling around the state, whether it’s taking a scenic fall drive through the Driftless Area in southwest Wisconsin, exploring the potholes and drumlins of Kettle Moraine State Forest near Milwaukee, or kayaking among the water-etched sea caves off Lake Superior’s Apostle Islands.

To the trained eye, those landscapes also tell a story, but one goes beyond a quick photo and may provide answers to important research questions. University of Wisconsin-Madison Professor Steven Loheide, graduate student Eric Kastelic, Freshwater@UW summer students Lucie Carignan and Ella Flattum, and collaborators are focusing their collective scientific gaze on a particular section along Door County’s southeast coast for clues to a decades-old question: How do Great Lakes water level changes affect groundwater and forests along our coasts?

The Ridges Sanctuary is a 1,700-acre nature preserve tucked along the bottom half of Door County as it pokes into Lake Michigan just above the community of Bailey’s Harbor. Initially established in 1937 as Wisconsin’s first land trust, the sanctuary is a National Natural Landmark noted for a rich concentration of rare plants, including 25 species of orchids. What really sets this place apart from other preserves, however, is the 30 or so swales and crescent-shaped ridges that line the sanctuary from west to east.

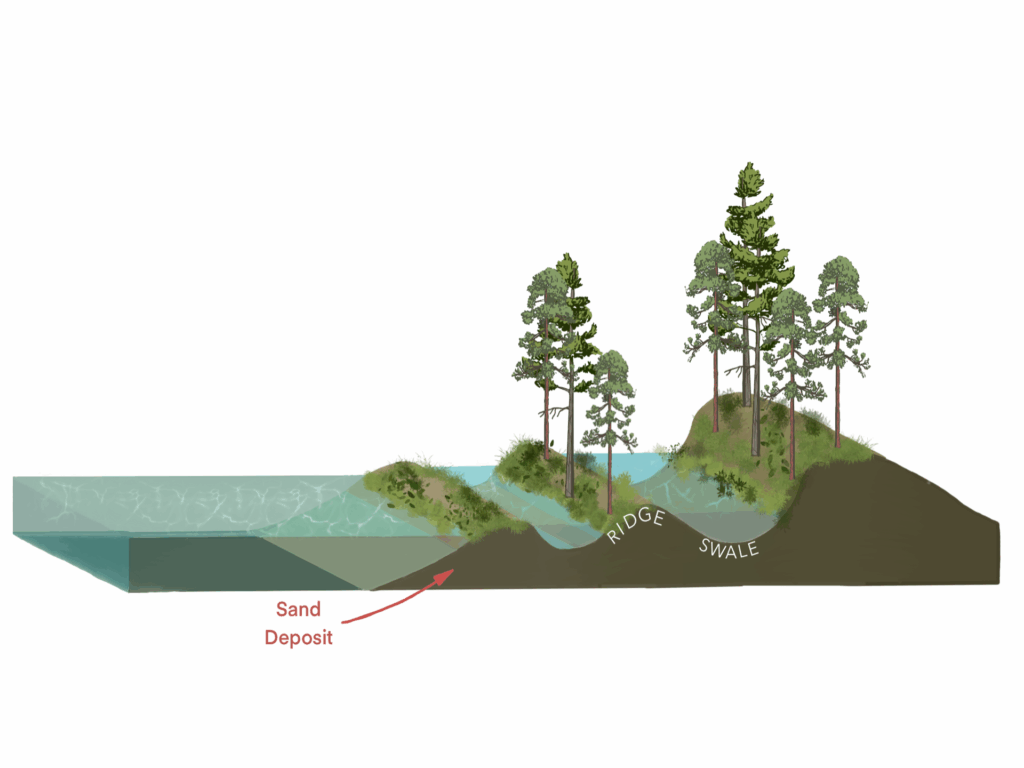

These are the areas where Loheide, Kastelic, and team have concentrated their efforts. The sandy formations represent former beaches caused by changes in Lake Michigan water levels during the past millennia. Each is peppered with black and white spruce, balsam fir, and white pine. Between these ridges are swales, which are wet, lower areas, each containing their own collection of diverse marsh and bog flora.

In ridge and swale ecosystems, forested ridges and marshy wetlands run in long strips parallel to the shore, like here at the Ridges Sanctuary.

“What we’re interested in is how the Great Lakes and the changing water levels within the Great Lakes affect the ridge and swale ecosystems,” said Loheide. “There’s a tight connection between the surface water, the Great Lakes, and then the groundwater, which is underneath the subsurface but is feeding the wetlands and feeding the forests in these systems.”

Scientists have known for some time that water levels fluctuate in all five Great Lakes. Historically they change not just annually but over several decades with the record high being more than 6 feet higher than the record low. For Loheide, what he and his fellow researchers are most interested in are more recent water level changes.

“On short, seasonal scales, you might have a foot of variability from high water levels in one year to low water levels in that same year,” explained Loheide. “But when you look at it at a longer time frame, we see that there are cycles. For instance, in the early 2000s through about 2012-2013, we were in a low water state. That whole time, there were still ups and downs every year, but we were at low water levels, and then we went from near record lows then to record highs in 2017, 2018, and 2019. That really quick swing is something that we’re interested in.

“There’s always been a lot of variability, but we’re seeing what seems to be sometimes faster changes from low water level conditions to high water conditions, so more extremes. And we’re actually going through the same thing right now,” said Loheide. “The high-water levels of 4-6 years ago are now dropping to below average water levels on Lake Michigan.”

Those faster water level changes could have greater impact on coastal ecosystems, and that’s where Loheide’s team has zeroed in their research efforts.

“Even since last year, lake levels have gone down about 10 inches. What does that mean for the groundwater system? Are we draining water out of the groundwater system? How much change in storage is there of our groundwater resource, and how does that affect other hydrologic and ecological processes?”

Great Lakes water levels impact the groundwater levels within ridge and swale ecosystems, as seen here in a cross-section created by Lucie Carignan.

Not just water and systems may be impacted, Loheide added. “We’ve been studying trees and groundwater in Wisconsin for over a decade now, and we’ve been surprised by some of the things we’ve learned, that groundwater is used by trees. Even in a wet climate like Wisconsin where we get a lot of rain, we’re seeing that trees, particularly if they’re in sandy soils that drain really quickly, do depend on shallow groundwater, and if they have access to shallow groundwater, they do better.”

Given we know Great Lake levels fluctuate and those levels are connected to our coastal ecosystems, the team is looking at the Ridges and those funky swales lining the landscape to help them sketch out the rest of the story. “Our interest in the swales is knowing that we have lake levels that are driving changes in groundwater levels, how does that affect the ecosystem?” Loheide noted. “How does that affect tree growth? How does that affect whether the forest might be vulnerable to either drought conditions where there’s limited water availability and the trees don’t have access to shallow groundwater, versus what happens during really high lake stages, and you end up with the roots of the plants being saturated, having low oxygen availability that can be fatal to the trees?”

The team has developed an ecohydrological observatory at The Ridges, which besides the cool name is also a great way to continuously monitor groundwater levels and changes that occur daily as the trees start to use water, from when the sun rises higher in the sky and exerts its considerable influence on the flora to when things start to shut down in the evening.

Loheide’s team, however, is looking beyond daily data. “We’re really hoping to leverage long-term data sets, and that’s coming from the trees themselves. If we core the trees, we can see variability in the annual growth. When conditions are good, when you’re getting the right amount of rain, when groundwater’s at the right level, we see larger growth rings. But, we see narrow growth rings during dry years or years where groundwater is not available, or even when groundwater’s too shallow,” said Loheide. “So that gives us an opportunity to not just have the data we collect during this two-year project, but to have a record that extends over a hundred years with some of these older trees.”

Graduate student Eric Kastelic and undergraduate researcher Lucie Carignan check in on a groundwater monitoring well that they installed at the Ridges Sanctuary, which gives them groundwater level measurements multiple times every hour.

By taking tree cores of red and white pine trees, the research team can analyze tree growth patterns going back almost 150 years.

The two-year project window Loheide references comes from funding through the Aquatic Science Center’s Water Resources Institute. Additional work was done by Joe Binzley (Hilldale Undergraduate Researcher 2025, UW-Madison) and collaborators from the Ridges Sanctuary, UW-Platteville TREES Lab, and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Loheide said that the findings his team develops could be used to better understand how extreme changes in water levels impact groundwater and flora not only at the Ridges but also for other areas throughout the Great Lakes.

“We’re hopeful that we can use remote sensing tools to try to compare other sites, and if satellite data can show us how transpiration or water use might be changing,” Loheide said. “There are new satellites out there that are at fine scale that we might actually be able to see and map out the spatial variability within ridge and swale wetlands, and then also compare among them what the response is.

“We’re excited about what the future holds.”

The post The Swale Tale first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/news/the-swale-tale/