A Wisconsin whitefish refuge offers lessons for Michigan. But will it last?

STURGEON BAY, WISCONSIN — It’s midmorning in late February, and Bruce Smith is regaling two ice fishing buddies when a tug on his line interrupts the story.

“There we go!” he shouts as a shimmering 23-inch whitefish appears through a hole in the ice. “That’ll make a nice filet.”

No sooner has Smith tossed it into a cooler than his buddy Terry Gross reels in another one. Five minutes later came another bite, then another, until by 10:30 a.m. the trio had hauled in 15 fish — halfway to their daily limit, even after putting several back.

Welcome to southern Green Bay. Or as Smith likes to call it, “Whitefish Town, USA.”

Once written off as too polluted to support many whitefish, the shallow, narrow bay in northwest Lake Michigan has produced an unlikely population boom in recent years, even as the iconic species vanishes from most of the lower Great Lakes. The collapse has dealt a blow to Michigan’s environment, culture, economy and dinner plates.

Oddly enough, nutrient pollution from farms and factories may help bolster the bay’swhitefish population, spawning a world-class recreational fishing scene while helping a handful of commercial fisheries in Michigan and Wisconsin stay afloat despite the collapse in the wider lake.

“This is a paradise,” Smith said. “The best fishing I can ever remember, for the species I want to catch.”

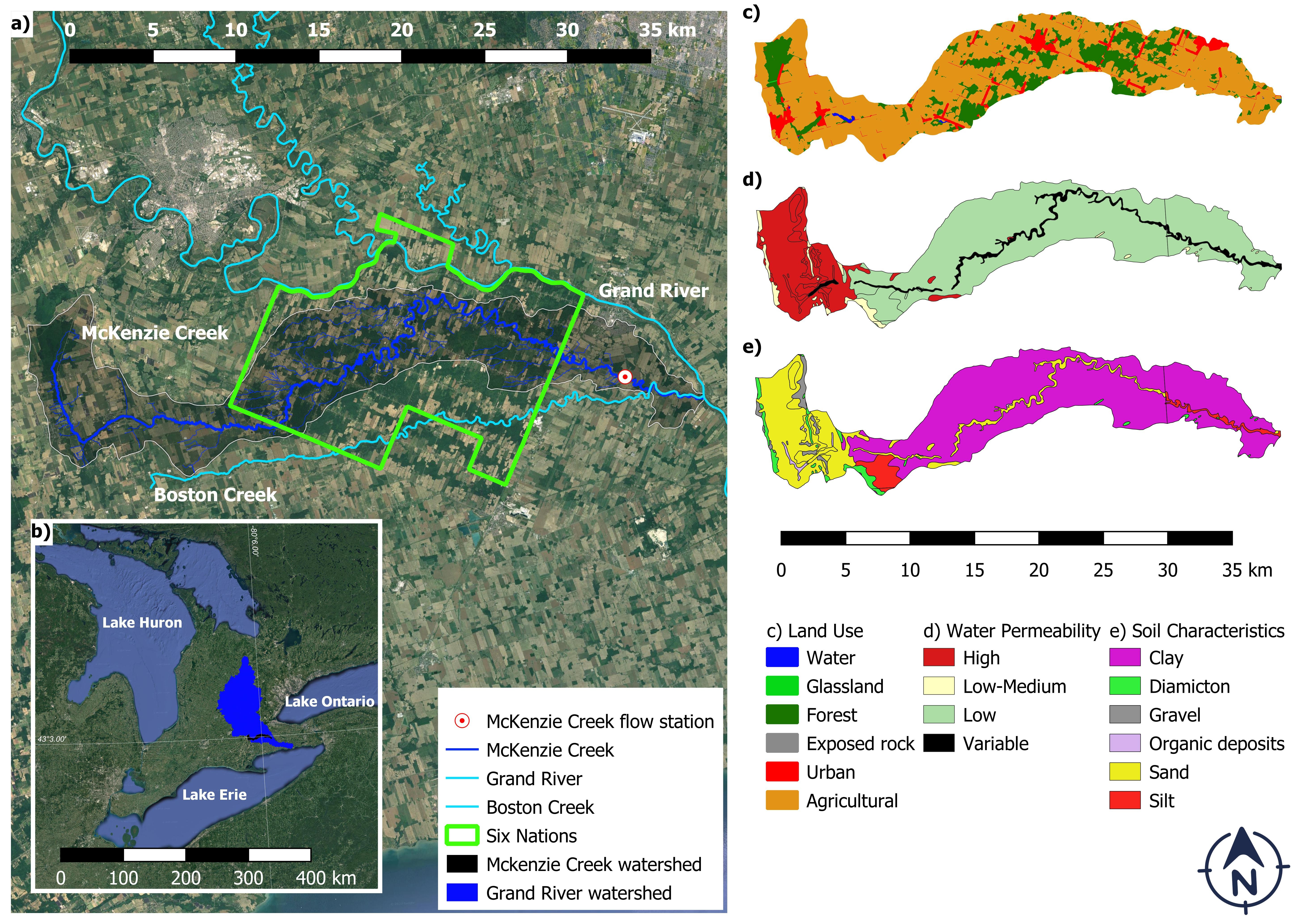

As scientists work to understand what makes Green Bay unique, their findings could aid whitefish recovery efforts throughout the Great Lakes. Michigan biologists, for example, have drawn inspiration from Green Bay’s sheltered, nutrient-rich waters as they attempt to transplant the state’s whitefish into areas with similar characteristics.

“Having places they (whitefish) are doing well … gives us context for the places that they aren’t doing well,” said Matt Herbert, a senior conservation scientist with the Nature Conservancy in Michigan. “It helps us to figure out, how can we intervene?”

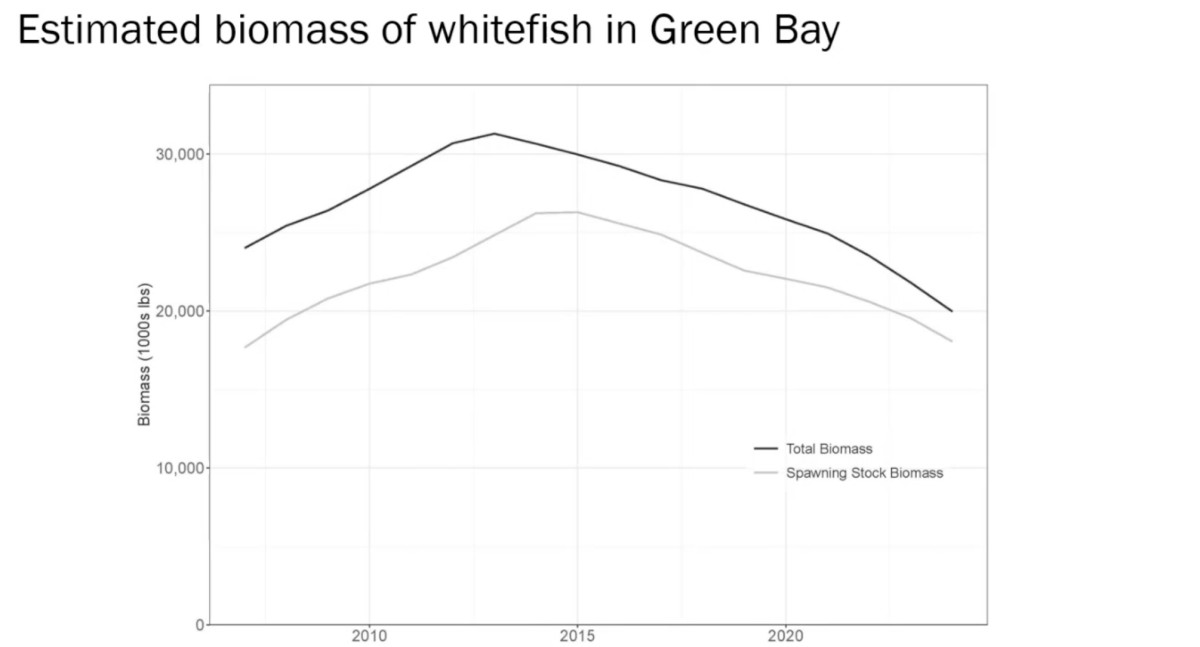

But lately, sophisticated population models have shown fewer baby fish making their way into the Green Bay population, prompting worries that Lake Michigan’s last whitefish stronghold may be weakening.

A Great Lakes miracle

Not long ago, it seemed impossible that a fishery like this could ever exist in Green Bay.

Before the Clean Water Act of 1972 and subsequent cleanup efforts, paper mills along the lower Fox River — the bay’s largest tributary — dumped toxic polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) into the water without restraint while silty, fertilizer-soaked runoff poured off upstream farms.

Southern Green Bay was no place for “a self-respecting whitefish,” said Scott Hansen, senior fisheries biologist with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Lake Michigan’s much larger main basin, meanwhile, was full of them.

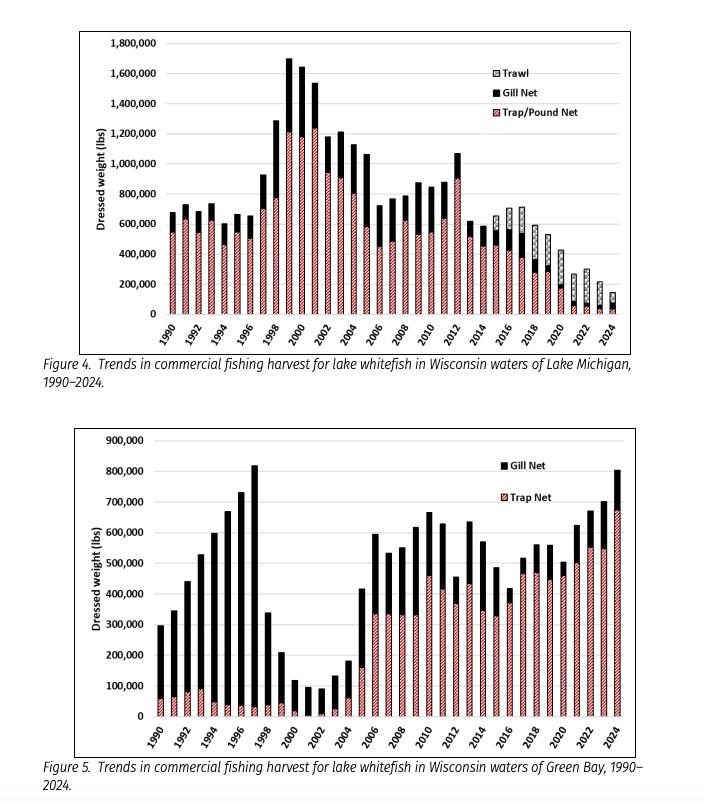

Commercial fisherman Todd Stuth’s business got 80% of its catch from the open waters of Lake Michigan before the turn of the millenium. Now, 90% comes from Green Bay.

How did things change so dramatically?

First, invasive filter-feeding zebra and quagga mussels arrived in the Great Lakes from Eastern Europe and multiplied over decades, eventually monopolizing the nutrients and plankton that fish need to survive. Whitefish populations in lakes Michigan and Huron have tanked as a result.

Fortunately for Wisconsin and a sliver of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, Hansen said, “Southern Green Bay kept building.”

In the late 1990s, scientists began spotting the fish in Green Bay area rivers where they hadn’t been seen in a century. Soon the species started showing up during surveys of lower Green Bay. By the early 2010s, models show the bay was teeming with tens of millions of them.

It’s not entirely clear what caused the whitefish revival, but most see cleaner water as part of the equation.

A decades-long restoration project has cleared away more than 6 million yards of sediment laced with PBCs and nutrient-laced farm runoff from the Fox River and lower Green Bay. Phosphorus concentrations near the rivermouth have declined by a third over 40 years — though they’re still considered too high.

“Pelicans are back, and the bird population seems to be thriving,” said Sarah Bartlett, a water resources specialist with the Green Bay Metropolitan Sewerage District, which monitors the bay’s water quality. “And now we have this world-class fishery.”

Hansen’s theory is that back when whitefish were still abundant in Lake Michigan, some wanderers strayed into the newly hospitable bay and decided to stay. Or maybe they were here all along, waiting for the right conditions to multiply.

Either way, the bay has become a lifeline for whitefish and the humans that eat them.

“I feel very fortunate that the bay is doing as well as it is,” said Stuth, who chairs the state commercial fishing board.

As commercial harvests in the Wisconsin waters of Lake Michigan plummeted from more than 1.6 million pounds in 2000 to less than 200,000 pounds in 2024, harvests in Green Bay skyrocketed from less than 100,000 pounds to more than 800,000.

The bay has also become more important to fishers in Michigan, which has jurisdiction over a portion of its waters.

While the state’s total commercial harvests from Lake Michigan have plummeted 70% since 2009 to just 1.2 million pounds annually, the decline would be steeper were it not for stable stocks in the bay. Once accounting for just a sliver of the catch, the bay now makes up more than half.

A recreational ice fishing scene has sprung up too, with thousands of anglers taking to the ice each winter, contributing tens of millions to the local economy.

Ironically, the bay’s lingering nutrient pollution may be helping to some extent – a dynamic also seen in Michigan’s Saginaw Bay.

Nutrients like phosphorus and nitrogen are the building blocks of life, fueling the growth of aquatic plants and algae at the base of the food web. Plankton eat the algae, small fish eat the plankton, and big fish eat the small fish.

Unlike the main basins, where mussels have hogged nutrients and starved out whitefish, polluted runoff leaves the shallow bays with more than enough for the mussels and everything else.

Some have even suggested Michigan and its neighbors should start fertilizing the big lakes in hopes of giving whitefish a boost, Herbert said, but “there’s the question of feasibility.”

First, because the lakes are far deeper and wider than the bays, it would take vast quantities to make an impact. And while excess nutrients may help feed fish, they could also cause oxygen-deprived dead zones, harmful algae blooms and other serious problems.

Green Bay is already offering other lessons for Michigan, though.

Inspired by whitefish’s return to the bay’s rivers, biologists including Herbert are trying to coax Michigan whitefish to spawn in rivers that connect to nutrient-rich rivermouths like Lake Charlevoix.

The hope is that if hatchlings can spend a few months fattening up before migrating into the mussel-infested big lake, they’ll stand a better chance of surviving.

Scientists in Green Bay are also tracking whitefish movements, hoping to figure out where they spawn and what makes those habitats special. That kind of information could prove useful to recovery efforts throughout the Great Lakes, said Dan Isermann, a fish biologist with the US Geological Survey.

Living in ‘the good old days’

“We’re really lucky to have what we have here,” said JJ Malvitz, a commercial fishing guide who owes his career to Green Bay’s whitefish resurgence.

But he lives with fear that “the good old days are now.”

Stocks have shrunk by half since the mid-2010s, according to population models fed with data from DNR surveys and commercial and recreational harvests. The adult whitefish seem to be fat and healthy. But for reasons unknown, fewer of their offspring have been making it to adulthood.

It’s possible the bay’s population is just leveling off after a period of strong recruitment, Hansen said, “but we want to be vigilant.”

A recent string of lackluster winters adds to the concern. Whitefish lay their eggs on ice-covered reefs. When that protective layer fails to form or melts off early, the eggs can be battered by waves or enticed to hatch early, out of sync with the spring plankton bloom that serves as their main food source.

While this winter was icier than most, climate change is making low-ice winters more frequent.

“Whitefish are a cold-water species, and we know that’s not where the trends are going,” Hansen said.

Time to cut back?

So far, Wisconsin officials haven’t lowered Green Bay’s annual whitefish quota of 2.28 million pounds, evenly split between the commercial and sport fisheries. Commercial boats are limited to fish bigger than 17 inches, while recreational anglers are limited to 10 fish a day of any size.

But during a recent presentation to the state’s Natural Resources Board, Hansen said it’s time to start keeping closer tabs on the population.

“If these trends continue,” he said, “We need to have some more serious discussions amongst ourselves about lowering the exploitation rates.”

Malvitz, the guide, believes it’s time for commercial and recreational anglers to collectively agree to harvest fewer fish. He would be satisfied with a five-fish limit for recreational anglers along with smaller quotas for the commercial fishery, which harvests far more fish.

The bay’s whitefish reappeared quickly and unexpectedly, he said. Who’s to say they couldn’t disappear just as fast?

“I don’t want to be standing on the shore in five years saying ‘remember when,’” he said.

Stuth, the commercial fishing board chair, isn’t ready to accept tighter quotas in the bay, but said population models should be closely watched. If the declines continue, he said, cuts may be on the table.

“A very conservative approach is going to be necessary,” he said. “Because it’s our last stronghold. If that goes away, what do we have?”

The post A Wisconsin whitefish refuge offers lessons for Michigan. But will it last? appeared first on Great Lakes Now.

Great Lakes Now

https://www.greatlakesnow.org/2026/03/12/a-wisconsin-whitefish-refuge-offers-lessons-for-michigan-but-will-it-last/