Join us for “Students Ask Scientists” on November 6

Should I Stay, or Should I Go: Tracking Partial Migration Frequency of Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens)

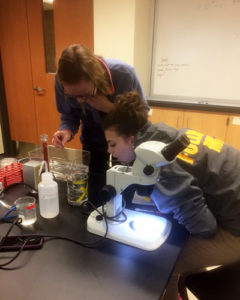

Anna Hill, submitted photo.

Studying fish comes with many challenges, and one of the biggest is that they are constantly on the move. Because of this, tracking fish has become a major focus in aquatic science in recent years. With tools like acoustic telemetry, scientists can now monitor fish movement at both fine and large spatial scales.

- When: November 6, 2025, 11-12 CT

- Target audience: Middle school students and up and their educators

- Please pre-register for Zoom-based event

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/news/join-us-for-students-ask-scientists-on-november-6/