Summer research student learns independence and patience while studying microplastics

Jena Choi, Freshwater@UW student, collects water from beaches for E. coli analysis later at the UW-Oshkosh Environmental Research and Innovation Center. Image Credit: Megan Jensik

By Jena Choi, Freshwater Collaborative summer research student

This summer, 35 undergraduate students from across the country conducted research with Freshwater@UW, the University of Wisconsin’s cross-site, cross-discipline research opportunities program. Freshwater@UW is supported by the Freshwater Collaborative, Wisconsin Sea Grant, Water@UW–Madison, the Water Resources Institute and the University of Wisconsin–Madison Graduate School. In the final weeks of the program, students reflected on what they learned. We are sharing several of their stories over the coming months. Here’s Jena Choi, an undergraduate sophomore in freshwater science from UW–Milwaukee, who worked with Greg Kleinheinz at UW–Oshkosh.

I stumbled across Freshwater@UW a year ago, and I’m pleased that my persistence landed me in this program. As someone who finds comfort in familiarity, this program was the right step to coming out my comfort zone and exploring research in a new laboratory.

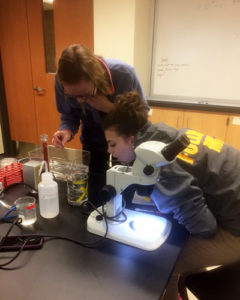

I had the privilege of working at ERIC (Environmental Research and Innovation Center) in the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, where I conducted my research in evaluating methods for analyzing microplastics from beach sand samples. Microplastics is a hot topic in the environmental field, and we’ve come a long way in developing several methods for analyzing them. The problem lies more in which methods to use and how effective they are at extracting tiny microplastics that you can’t even see with the naked eye.

Choi reads water temperature for weekly beach data reports. Image Credit: Megan Jensik

One key lesson I’ve learned about research is that it involves a lot of reevaluating, revising and importantly, retrying. Rather than picking up another person’s project, I had to start from the beginning. I navigated through the seas of different methods from other scientific journals while remodifying them several times to fit both my limited time and resources. Once I settled with a method proposed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the true battle was finding and ordering everything before I could start my project. The process required a lot of patience and persistence, especially when the methods didn’t show promising results. However, all these moments gave me great insight on what graduate level research would look like, as well as a key lesson in being independent.

A density separation setup in the lab to separate settled solids from floating solids (microplastics). Image Credit: Jena Choi

I also learned that being part of the Freshwater@UW program is more than research. It also branches into helping communities and learning different career opportunities. Not only does ERIC host research projects, but they also test samples for campus members and external clients. I was able to help people know if their drinking water is safe and alert them of any possible dangers. Another welcome surprise were my weekly beach routes where I collected beach water around Winnebago County to test for E. coli. If the beaches reached a concerning level, it was our duty to warn the public by putting up signs and informing the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources about the elevated levels of E. coli. Based on these experiences, I can see myself working in both a field and lab setting while working with the public through education and science communication.

I’m grateful that Freshwater@UW has given me the opportunity to explore research in UW-Oshkosh. I’ve not only pursued my interest in microplastics, but I’ve learned the valuable skills of constructing my own project and independently solving any related conundrums or mistakes. With everything I’ve learned, I see my career heading to a professional track and hope to use the skills I’ve learned to improve Wisconsin’s water.

The post Summer research student learns independence and patience while studying microplastics first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.Blog | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/blog/summer-research-student-learns-independence-and-patience-while-studying-microplastics/