Watch: How tree rings and community conversations are bringing fire back

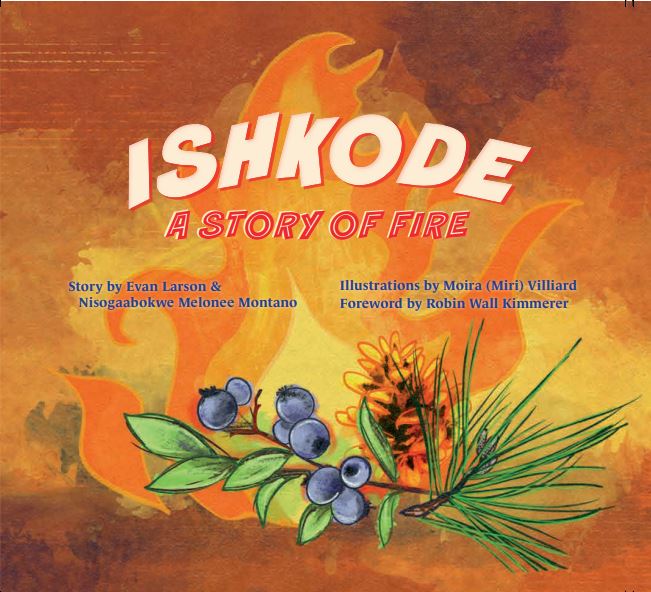

Research into centuries-old fire-scarred trees in northern Wisconsin is helping shape current fire management practices for tribal and state partners. The project, We are all gathering around the fire, or Nimaawanji’idimin giiwitaashkodeng in Anishinaabemowin, combines dendrochronology, Native Experiential Knowledge (NEK), and community engagement to uncover the intertwined ecological and cultural history of this Lake Superior coastal landscape.

The two-year Wisconsin Sea Grant-funded project, featured in a new video, confirmed something long known in Indigenous communities but rarely acknowledged in scientific literature: the beloved red pine forests on Wisconsin and Minnesota Points were not shaped by nature alone, but by people who used fire to care for the landscape. Red pine struggles to produce new generations without fire.

Wisconsin and Minnesota Points are Lake Superior coastal peninsulas off the shores of Duluth, Minnesota, and Superior, Wisconsin.

Dendrochronologist and Professor Evan Larson sands a wood sample to get it ready for the microscope.

The exclusion of Indigenous perspectives and burning practices in the forest management has led to reduced ecosystem resiliency, biodiversity, and a drop in the pine tree population. In order to prove that people, and not natural phenomena like lightning, set fires to the landscape, the team looked for centuries-old fire scars from tree samples collected on the Points. The data confirm what the team expected.

“The fires on both Points ceased abruptly after the signing of the 1842 and 1854 treaties,” said Evan Larson, professor at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. “It is undeniable that the reason that we love the Points and protected the pine forest is because of the fires that people were setting,” Larson said. “That act of ‘protecting’ – moving people out of that space – is literally dooming the things that we’re hoping to protect.”

After two years of research, engagement, and outreach, the team has shown the importance of fire and NEK to Wisconsin and Minnesota Points. This has allowed them to take important steps to return cultural fire to the landscape.

Melonee Montano, project leader and University of Minnesota-Twin Cities Forestry Department graduate student, talks about the deep significance that Wisconsin and Minnesota Points hold to the Anishinaabe people.

Fire helps red pines, like the ones pictured here on Wisconsin Point, regenerate.

“One thing that has made this research extremely successful is the funding from Wisconsin Sea Grant, because that’s been our starting point for all of this,” says project and tribal leader Melonee Montano. Throughout the project, Larson, Montano, and their students talked to local residents about the history of fire and the possibility of returning it. “The funding made it possible for us to go out and actually build these relationships on the ground, in people’s homes, at their kitchen tables, and at the city meetings.”

Larson and Montano have been surprised by the amount of support they’ve gotten from the community. “Through this work, we’re seeing, in ways that I can’t put into words, that it’s time for fire to come back,” says Montano. The city of Superior is now in advanced discussions with fire experts from the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa about burning practices on Wisconsin Point.

“A lot of this really has only been possible because of this grant, which is really weird for my mind to process,” reflects Montano. “It’s strange to think that it took a grant – a piece of paper, some money – to bring these folks together to actually start tearing down through the layers of trauma to figure out what is at the base and what really happened.”

While the Sea Grant funding has come to a close, the team continues their work supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation. They will be broadening their research to encompass the whole Great Lakes region.

The post Watch: How tree rings and community conversations are bringing fire back first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/news/watch-how-tree-rings-and-community-conversations-are-bringing-fire-back/