A new use for an old technology

Reverse osmosis membranes could revolutionize nanoplastic sampling in the Great Lakes

Nanoplastics continue to build up, largely unnoticed, in the world’s bodies of water and inside people’s bodies. Image of Lake Mendota by Marie Zhuikov, Wisconsin Sea Grant.

The target is small. Very small. Researchers have shined the light on environmental dangers posed by microplastics – small pieces of plastic from clothing and packaging that pollute waterways. Now, however, they are also focusing on nanoplastics, which are even smaller plastic particles – invisible to the naked eye and even under a regular microscope, and smaller in diameter than a human hair.

Linked to cardiovascular and respiratory diseases in people, nanoplastics continue to build up, largely unnoticed, in the world’s bodies of water and inside people’s bodies. They’re everywhere. Researchers think nanoplastics may be more harmful than microplastics because, “The smaller their size is, the higher toxicity they have,” said Haoran Wei, assistant professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “There’s a higher surface area on nanoplastic particles, which can accumulate more toxic chemicals and other contaminants on their surfaces. They’re small enough to get into living cells, so can directly harm creatures in the Great Lakes.”

Unfortunately, the presence and distribution of nanoplastics in the Great Lakes is still largely unknown. One reason is that current sampling methods are onerous – requiring collection and transport of hundreds to thousands of gallons of water from the lakes into the lab for analysis.

There’s got to be a better way, right? Thanks to Wisconsin Sea Grant funding, Wei and Mohan Qin, also an assistant professor at the department of civil and environmental engineering at UW-Madison, are working to solve the problem by looking at a new use for an old technology.

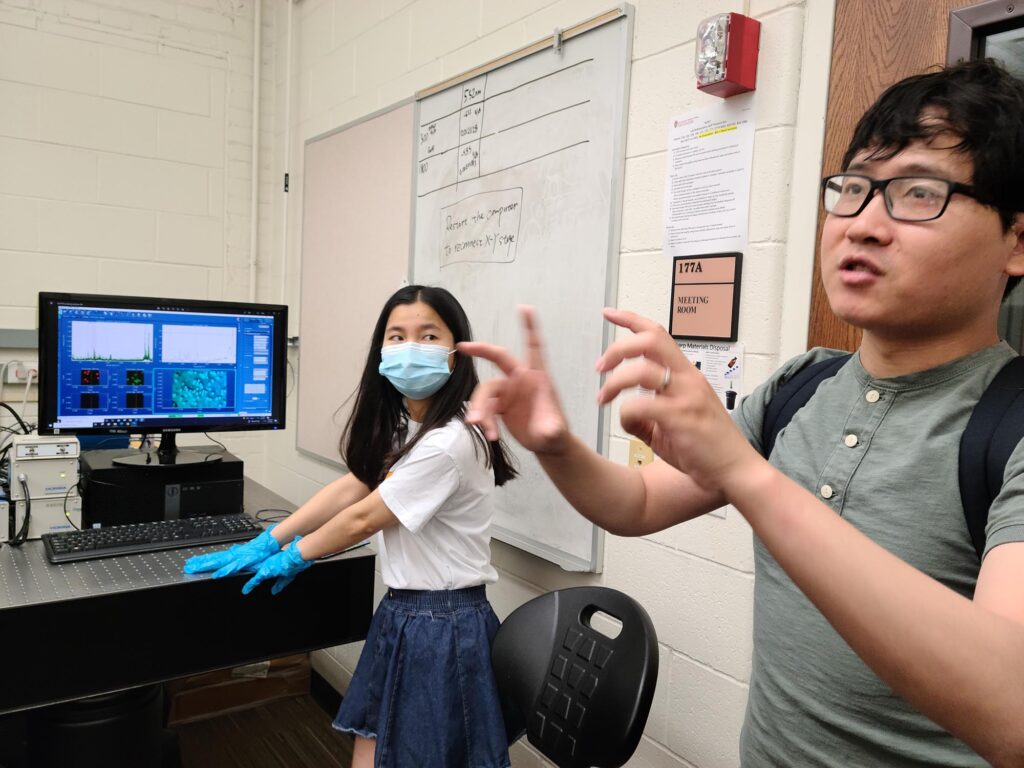

Haoran Wei (right) explains how microplastic and nanoplastic samples are analyzed in the lab while Ziyan Wu, a Ph.D. student on the project, watches. Image credit: Marie Zhuikov, Wisconsin Sea Grant

Desalinization plants have long used semipermeable membranes to take salt out of seawater through reverse osmosis. The membranes, made of polymers, have tiny pores that allow pressurized water to flow through them but catch things like salt. They can also catch nanoplastics. Qin and Wei are developing a portable membrane filtration device that researchers can use on a ship to process large volumes of water out on the lake instead of bringing the water back to the lab. They’ll collect the nanoplastics on a series of membranes and just bring those, or a concentrated water sample, back to the lab for analysis.

Sarah Janssen, a supervisory research chemist with the U.S. Geological Survey, is going to help Qin and Wei with the project this summer in coordination with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to collect water samples on their Lake Explorer II research vessel from lakes Superior and Ontario. But before they head out on the ship, they’ll test the membrane filter device with purified water in the lab and later with water from some local lakes, like Lake Mendota.

Mohan Qin describes environmental issues caused by nanoplastics while standing next to a different plastics research project conducted atop the Limnology Building at UW-Madison, which looked at how light degrades microplastics. Image credit: Marie Zhuikov, Wisconsin Sea Grant

Wei said that if successful, their project will be the first to develop a sequential membrane filtration sampler that collects and concentrates nanoplastics from a large volume of lake water. “And we definitely will be the first ones to carry this filter on a boat in connection with nanoplastics,” he said.

Qin and Wei will be helped by four college students and hope this method can be used by other agencies and water industries for microplastic and nanoplastic sampling. They also plan to work with Sea Grant’s Emerging Contaminants Scientist, Gavin Dehnert, to bring information about the project to Tribal communities and to participate in events like UW-Madison’s Day at the Capitol. “All my students love Capitol Days,” said Qin. “They will have the opportunity to work with people from the real world and talk about the problems researchers are working on.”

This project is related to a microplastics and food web project that Wei leads which was recently funded by NOAA. He said the goal of that project is to figure out if microplastics and nanoplastics can get into the Great Lakes food web. “We want to see if they get biomagnified up the food chain,” Wei said. “We’re going to do a lot of analysis and bioaccumulation experiments.”

The post A new use for an old technology first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/news/a-new-use-for-an-old-technology/