Lake and river foams study reveals high PFAS levels, even though underlying water may be less contaminated

Foam on Lake Monona. Image credit: Doug Bach

A new study of natural foams and water surface microlayers of 43 Wisconsin rivers and lakes quantified 36 compounds in a group of chemicals known as PFAS. While PFAS were detected in both types of samples, it is the foams that the researcher said were “orders of magnitude higher in PFAS concentration compared to water,” while urging people and their pets to avoid them. The study also revealed that foams, generally off-white and found along shorelines on windy days, are not an indicator of elevated contamination levels in the entire water body.

“We studied many different lakes and found PFAS in all of them. The PFAS concentrations were high in the foams even if the concentrations in the water were relatively low,” said Christy Remucal with the University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and interim director of the University of Wisconsin Aquatic Sciences Center.

Remucal stressed the need to avoid the foams because of the contaminants’ warning-worthy levels. “The chemical we found most in the foam is PFOS, which is one of the chemicals that’s driving fish advisories and driving drinking water regulations,” she said. “The highest PFOS concentrations we measured in foam were almost 300,000 nanograms per liter and, for comparison, the federal drinking water regulation is 4 nanograms per liter.”

She continued, “The main way people are exposed to PFAS is through ingestion…Obviously, people aren’t drinking foam. I would be more concerned about, for example, a kid who plays in the foam and then goes to grab a handful of snacks. You could potentially have some oral exposure that way.”

There are more than 9,000 PFAS compounds, which are often referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not readily break down in the environment. For decades, they have been used to make a wide range of products resistant to water, grease, oil and stains and are also found in firefighting foams, which are a major source of environmental PFAS contamination. PFAS have been shown to have adverse effects on human health and higher incidence of cancer.

The levels in the new study validate a current Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources warning, as well as a similar freshwater foam warning in Michigan and one for saltwater foam in the Netherlands. They are timely cautions as spring and summer come to Wisconsin and people and their pets spend more time hiking along open water or engaging in paddle sports and swimming where foams can be found.

Remucal, postdoctoral co-investigators Summer Sherman-Bertinetti and Sarah Balgooyen and graduate students Kaitlyn Gruber and Edward Kostelnik published their work in the journal “Environmental Science & Technology.” It was funded by a grant from the Wisconsin Sea Grant College Program.

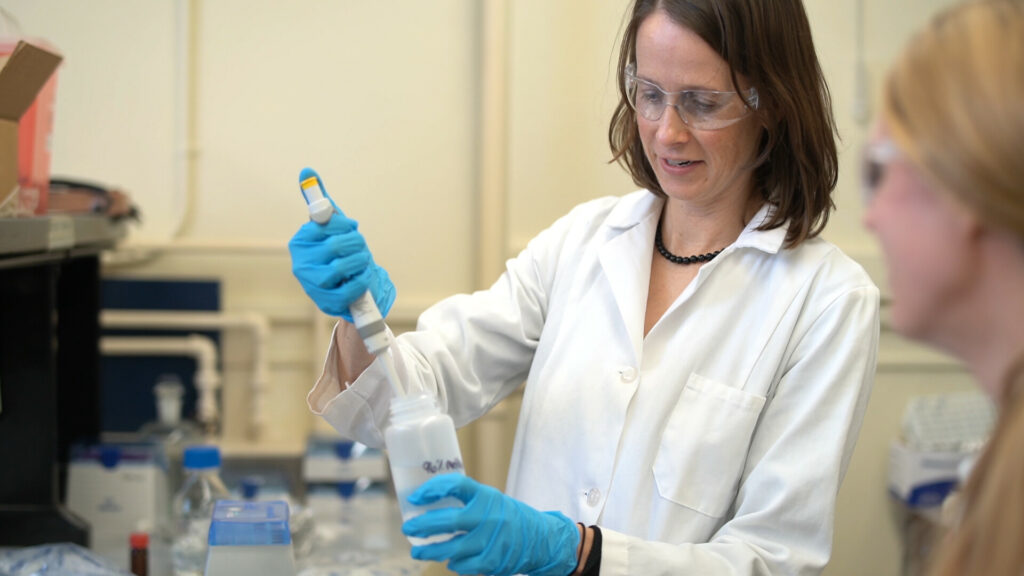

Christy Remucal and Sarah Balgooyen work with PFAS samples in the lab. Image credit: Wisconsin Sea Grant

Integral to the study were dozens of citizen volunteers who alerted the research team to the presence of foams. This was critical, Remucal said, because sampling was opportunistic—foams are fleeting, stirred up by wind and mixing with water, they can dissipate as quickly as they appear.

She also credited the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources with assistance in foam sightings.

The work also illuminates the efforts of other research groups exploring a possible path of PFAS cleanup. Because PFAS are surfactants, which means they are drawn to the air and water interface, they may move out of the water below and toward the bubbles in foam. When concentrated like this, the contaminants could be removed.

Remucal and her team also looked at water surface microlayers and found PFAS levels were slightly higher than underlying water but that the bigger take-away message remains the contaminant level in foams. She was pleased they explored the microlayers question, though, because the air and water interface dictates how PFAS move in groundwater. Now, the science community has an understanding of how PFAS movement in surface water compares to their movement in groundwater.

The post Lake and river foams study reveals high PFAS levels, even though underlying water may be less contaminated first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

News Releases | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/news/lake-and-river-foams-study-reveals-high-pfas-levels-even-though-underlying-water-may-be-less-contaminated/