Lessons in wild ricing and wild rice lake restoration

Science Communicator Marie Zhuikov attended a Wild Rice Symposium recently, along with hundreds of other people. Image credit: Marie Zhuikov, Wisconsin Sea Grant

Wisconsin Sea Grant sponsored a recent symposium on wild rice, which I had the chance to attend as did Deidre Peroff, our social science outreach specialist. The “Manoomin/Psin Knowledge Symposium” was held at the Black Bear Resort in Carlton, Minnesota, in mid-November.

The manoomin display that Wisconsin Sea Grant and Nature Conservancy staff helped create. Image credit: Marie Zhuikov, Wisconsin Sea Grant

Symposium-goers were offered instant inspiration by a large manoomin display at the registration table, which was created by Peroff, our creative manager Sarah Congdon, and Kristen Blann with The Nature Conservancy.

Most interesting were sessions where speakers described what wild rice means to them and tips for harvesting it.

Here are seven key things to keep in mind when harvesting wild rice in the fall and the names of the people who offered the advice:

- Unprocessed wild rice features a long tail-like barb that can have uncomfortable consequences for unwary harvesters. It can sometimes get stuck in people’s tear ducts, requiring careful extraction! If this happens to you, you’ll be crying “warrior tears.” (Donald Chosa, Bois Forte Band of Chippewa)

- Harvesters sometimes also inhale the rice and the barbs get stuck in their throats, making it hard to breathe and eliciting coughing. It’s a good idea to bring bread along while harvesting in case this happens. Eating the bread can dislodge the rice barb from a person’s throat. (Deb Connell, ricer, Lac du Flambeau)

- “Don’t harvest rice at your convenience. Harvest it when it’s ready.” (Todd Haley, Lac du Flambeau Band of Ojibwe)

- If your canoe tips over while ricing, it does not have any special Ojibwe cultural meaning other than, “It means you’ll get wet!” (Donald Chosa, Bois Forte Band of Chippewa) (I was especially keen on this information after my recent “immersive” wild rice experience.)

- Lift weights to strengthen your arms for ricing for about a month beforehand. (Donald Chosa, Bois Forte Band of Chippewa)

- Having music playing in the canoe makes the ricing day go faster. (Various speakers)

- The best way to learn how to rice better is to copy someone’s movements who is a good ricer. (Donald Chosa, Bois Forte Band of Chippewa)

I also learned about three projects in Wisconsin that were successful in bringing wild rice back to lakes where it had disappeared. These involved Spur Lake (Oneida County), Clam Lake (Burnett County), and Spring Lake (Washburn County).

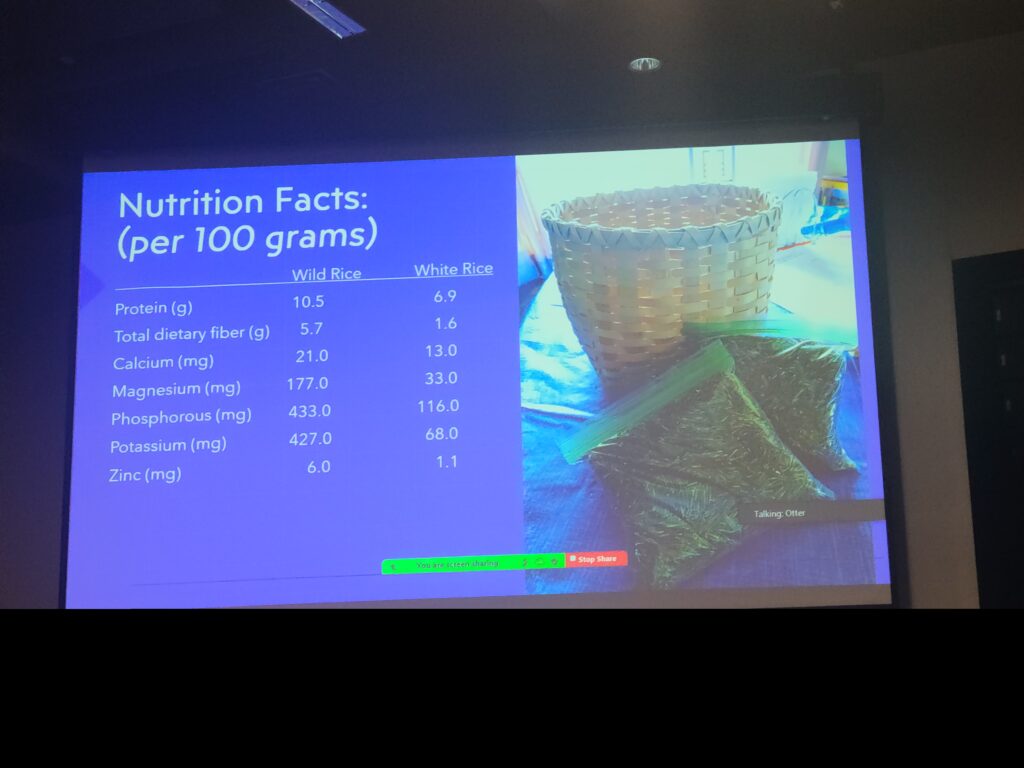

Nutritious wild rice is a true super food when compared to white rice, as noted in this image from one of the symposium speakers.

Carly Lapin with the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) said that Spur Lake, a historically important wild rice lake, began having trouble in 2009 when water levels became too high for wild rice to grow. She attributed this to beaver population recovery in the area and human alternations of the landscape. Also, aquatic invasive plant growth was out competing the wild rice.

Lapin said the DNR conducted a hydrologic study on the lake in cooperation with the Sokaogon Chippewa community to determine what was causing the water retention. In 2021, resource managers took advantage of naturally low water levels to remove competing vegetation with a mechanical harvester. The next year, they seeded the lake with wild rice and protected several plots with fencing to keep swans from eating the rice shoots. The protected areas grew successfully. A stream (Twin Lakes Creek) that provided outflow from the lake was restored and a harvest was able to occur in 2023.

Tony Havranek, an engineer with WSB, which is a design and consulting firm from Minneapolis, described the Clam Lake and Spring Lake projects. Clam Lake features two parts, an Upper and Lower Clam Lake. The lower part traditionally had wild rice, which declined from 2001-2009. In 2007 and 2008 the lake failed to grow any rice, which concerned the St. Croix Tribe. The tribe undertook studies with partners, who discovered that a steep rise in the population of common carp in the lake was the likely culprit. The age of the carp corresponded to the beginning of the rice crop failure. Havranek said the lake was home to 79,000 individuals, which equaled 670,000 pounds of fish.

“This is four times the tipping point for the lake environment,” Havranek said.

An integrated pest management plan was developed. Actions included installing barriers (nets) around the wild rice beds to keep out the carp, removing the carp from the lake and seeding the beds with local wild rice. Havranek said that over several years, 76,000 carp were removed.

By 2017, rice abundance had increased. Originally, 288 acres of rice beds were in the lake. By 2017, 177 acres had regrown, and harvest was able to begin again.

A successful wild rice harvest. Image credit: Thomas Howes, Fond du Lac Resource Management

Wild rice recovery at Spring Lake is still a work in progress. Problems began in 2000 when the outlet of the lake was changed. Floating leaf vegetation began taking over the lake. Herbicide was applied and unwanted plants were physically removed. After these actions, in 2005, rice was harvested.

However, rice production has declined recently (2016) due to cattail encroachment on the rice habitat. The cattails were mechanically removed and used for compost. Havernak said the rice harvest returned in 2017-2020 but that the lake is still struggling with rice production.

“We hope to remove more cattails and then put the lake on a monitoring schedule,” Havernak said.

Peroff and I staffed a table of publications at the symposium, which included our “ASC Chronicle” newsletter and a wild rice poster that features Ojibwe names for the different life stages of wild rice. The poster was very popular. It’s available online for free download here, or if you want a professionally printed version, you can contact Peroff at dmperoff@aqua.wisc.edu.

I left the event with a new appreciation for the complexities of wild rice management and harvesting. For a foraged food that’s strong enough to cause “warrior tears” or even choking, it remains incredibly fragile and needs our attention and care.

The post Lessons in wild ricing and wild rice lake restoration first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.Blog | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/blog/lessons-in-wild-ricing-and-wild-rice-lake-restoration/