Learning about Manoomin

Summer Outreach Scholar students Sarah Zieglmeier, Adam Gips and Gweni Malokofsky canoe to learn about ecological monitoring and a Manoomin restoration/reseeding project. Image credit: Deidre Peroff, Wisconsin Sea Grant

The calendar has flipped to 2024. Our staff members are already tackling new projects. Before they move too deeply into the new year, however, some staff members took a moment to retain the glow of their favorite 2023 project. Deidre Peroff, social science outreach specialist, shared her thoughts.

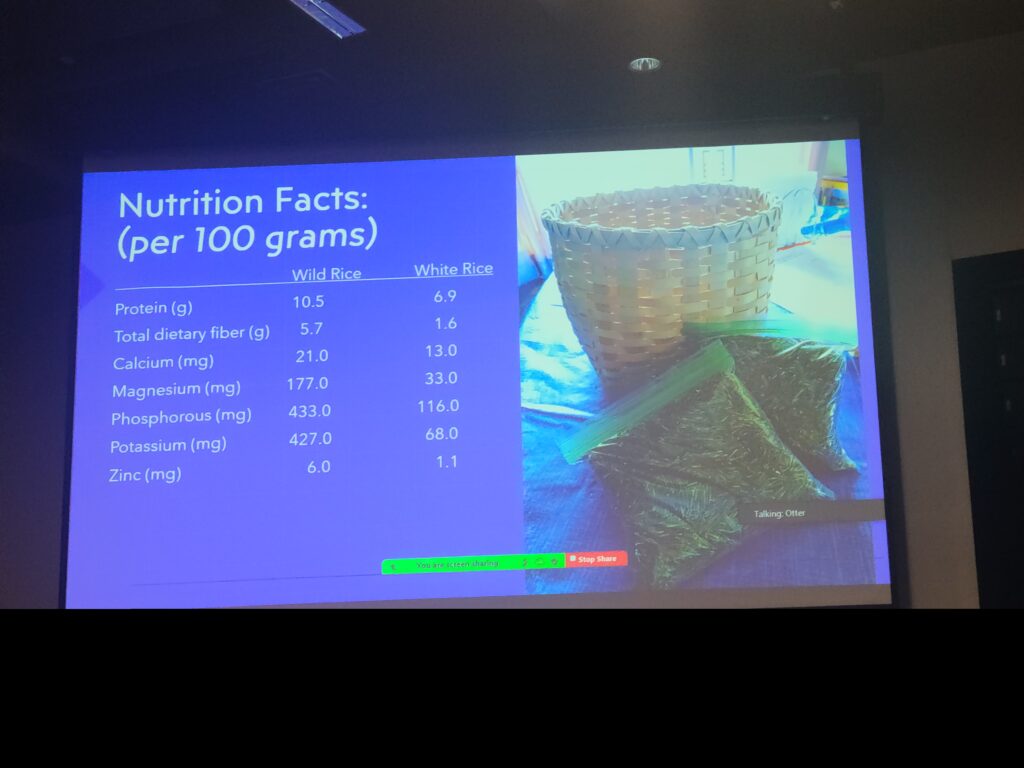

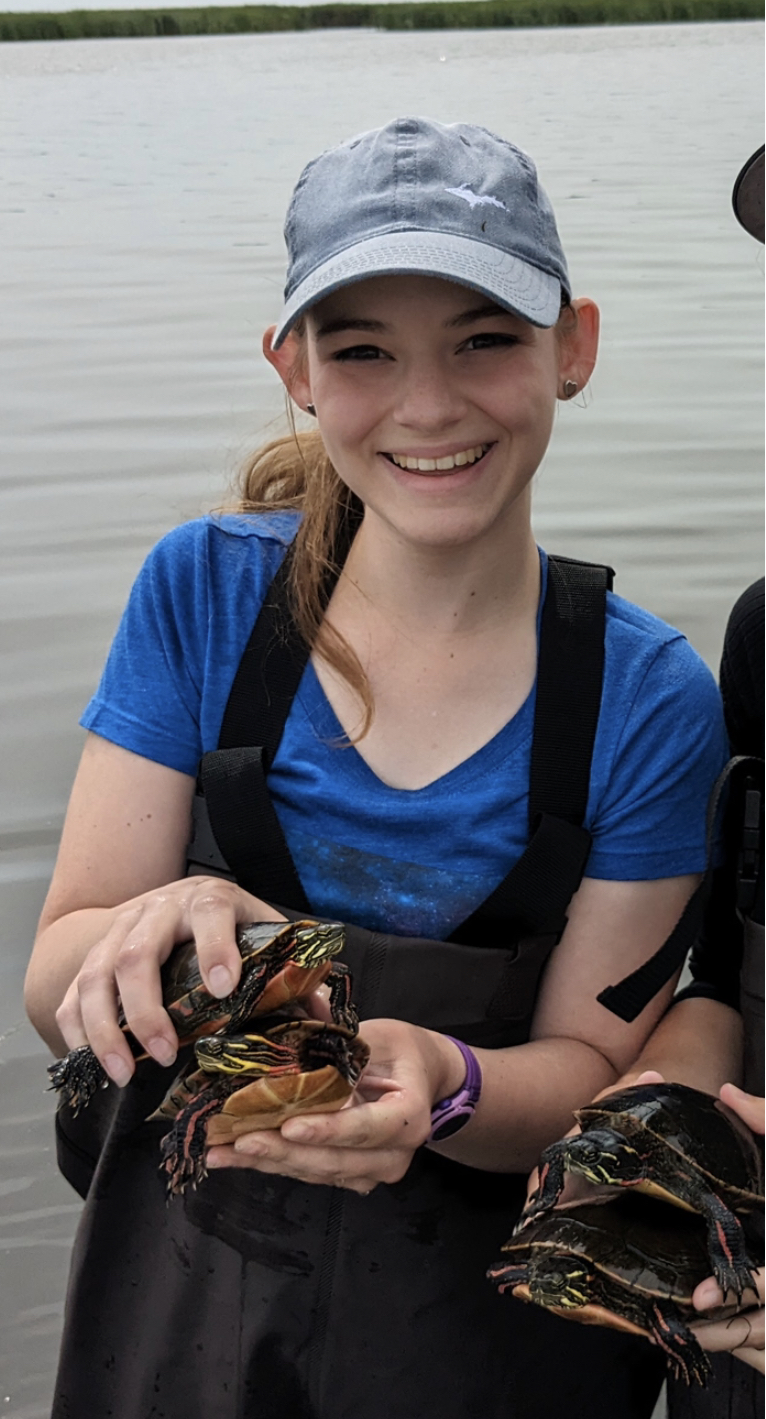

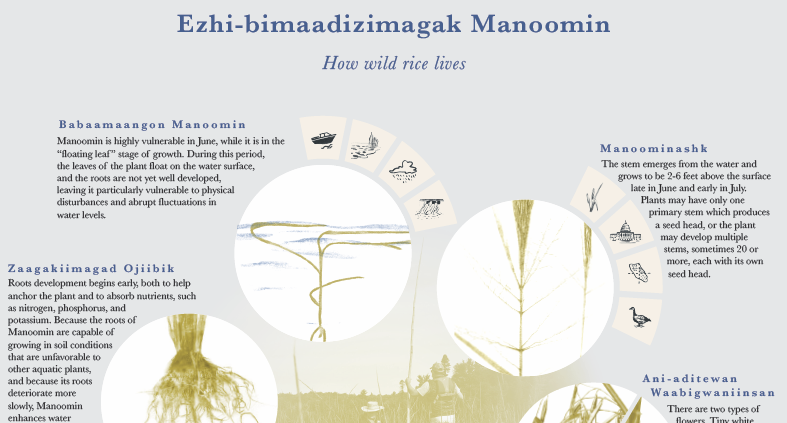

My favorite project from 2023 was when I took seven “Generation Z” students who are studying Manoomin (wild rice) camping near Green Bay. I was mentoring two of the students as part of Wisconsin Sea Grant’s Summer Outreach Scholar Program and the other five came from the University of Minnesota. They were also studying Manoomin and participating in summer Manoomin-related field excursions.

The Summer Outreach Scholar group enjoys an ice cream stop after a day trip. Pictured, left to right, front row: Elliot Benjamin, Adam Gips, Pipper Gallivan. Back row: Sashi White, Lucia Richardson, Deidre Peroff, Sarah Zieglmeier, Kane Farmer. Image credit: Deidre Peroff, Wisconsin Sea Grant

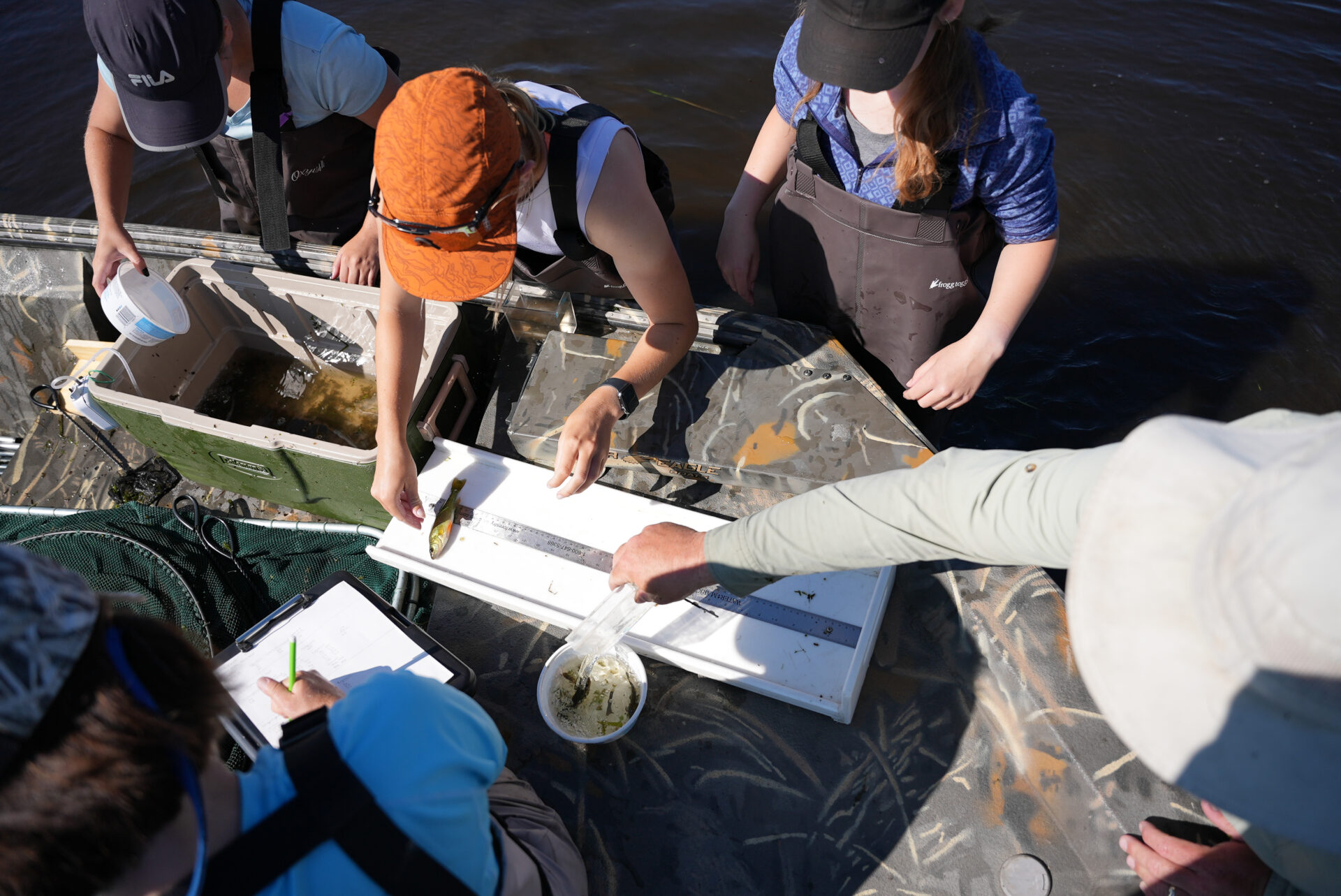

During four jam-packed days, we learned from Indigenous knowledge-holders about the significance of Manoomin and visited sacred cultural sites on the Menominee Indian Reservation. We met with Amy Corrozino-Lyon (University of Wisconsin-Green Bay restoration scientist) and Titus Seilheimer (Sea Grant fisheries outreach specialist) one day to learn about ecological restoration efforts of Manoomin in Oconto and did journal and poetry writing to better connect with a new plant (inspired by Robin Wall Kimmerer’s work, “Braiding Sweetgrass”). We also met with Jesse Conaway (who is working with the Brothertown Nation on another Sea Grant-funded project) to participate in a traditional Manoomin appreciation ceremony, plus we saw how drones are used for monitoring Manoomin in the Lake Winnebego region.

While the students learned so much, what I think we all appreciated the most was spending time together and getting to know each other. During our three nights camping, we enjoyed cooking meals together, playing cards, telling stories by the campfire and swimming in Lake Michigan.

At night, we reflected on what we had learned that day and I enjoyed seeing the students’ newfound understanding and appreciation of Indigenous knowledge and finding a balance between Western and Indigenous science approaches to conservation, restoration and monitoring of a cultural, spiritual and ecological keystone species. When we weren’t reflecting on what we were learning during the day, we enjoyed sleeping under the stars (and storms) and finding time to decompress in nature.

The post Learning about Manoomin first appeared on Wisconsin Sea Grant.

Blog | Wisconsin Sea Grant

https://www.seagrant.wisc.edu/blog/learning-about-manoomin/